The Usual Arteries

Erin Dorney

Illuminated Press

2024

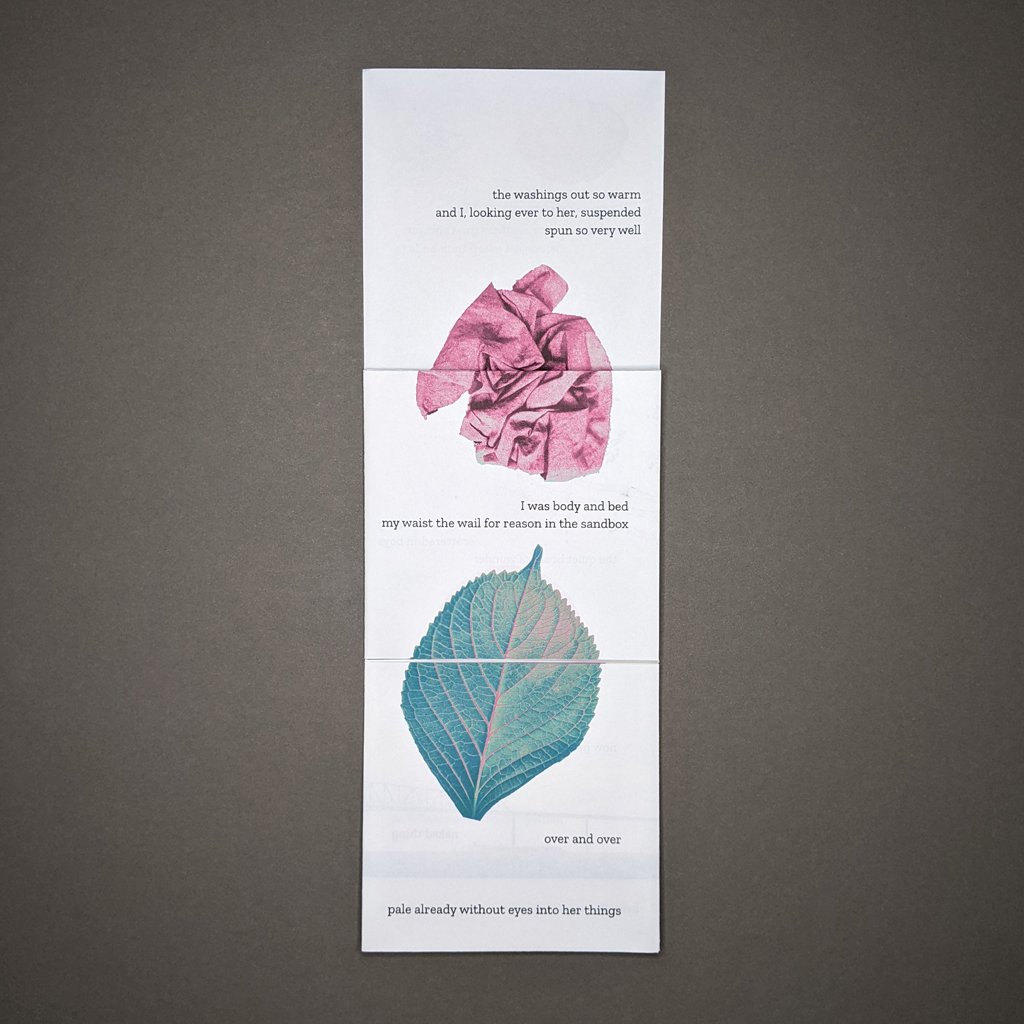

4.25 × 4.25 in. folded

Single cut and folded sheet in a paper slipcase

Ink jet inside with letterpress and screen printed slipcase

Edition of 250

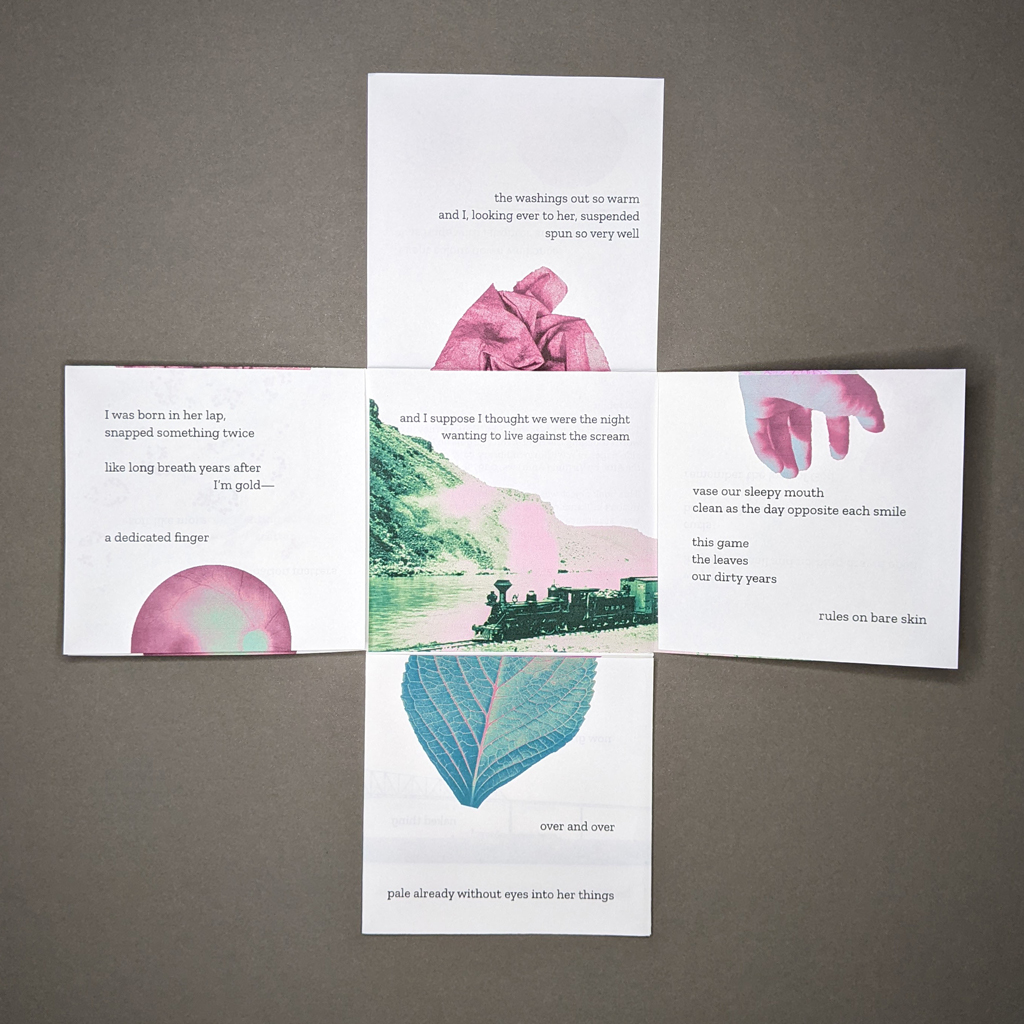

The Usual Arteries is a single illustrated poem on a single sheet of paper that nevertheless unfolds into a captivating reading experience that thoughtfully engages the book as a physical object and cultural touchstone. Dorney, both a poet and visual artist, draws the text exclusively from words set against the right-hand margins of a copy of Flowers in the Attic by V. C. Andrews, a controversial but wildly popular gothic novel first published in 1979. This interest in the physical space of the page extends to The Usual Arteries, whose eighteen square pages (the book is a two-sided, three-by-three grid with cuts that separate the pages but leave the sheet intact) allow the text to be read in more than one order. Without page numbers, the reader’s unfolding and refolding are guided by the book’s duotone illustrations, which are split across pages and can thus be matched up to form complete images. Because unfolding and refolding take concentration, and because the full poem is never visible all at once, the book would warrant repeated readings even without the multiple horizontal and vertical sequences permitted by its grid format.

Readers won’t need to have read Flowers in the Attic to enjoy The Usual Arteries. I haven’t read Flowers in the Attic, but a summary of the plot makes me think readers familiar with it will have a different experience with The Usual Arteries. (In fact, I’m glad I read The Usual Arteries a few times before investigating the source text.) The salacious story of incest, inheritance, and murder seems to stick with people. For her part, Dorney retains the original text’s first-person perspective and oblique references to a few characters, but these breadcrumbs in no way overdetermine the poem. If a certain darkness lingers beneath the surface, the credit must go to Dorney, not Andrews. The mood is fitting but not dependent on the original. Dorney alludes to past events without offering the clarity of narrative, unsettling but not upsetting the reader. Dorney has a knack for choosing words that are loaded but still open to recontextualization, and the way The Usual Arteries unfolds — sequential and combinatorial — allows for those changes in meaning no matter what background knowledge the reader brings with them.

The book’s photographic imagery adds another layer of open-ended associations, and while the text sometimes anticipates the imagery, the former is more than a caption, and the latter is more than an illustration. The images begin as single objects against the white background: a garment, a leaf, a flower. As the book progresses, larger images are collaged together, filling the page with lurid magenta-mint duotones that further the psychedelic effect of the content. Or perhaps the surrealist game exquisite corpse is a better comparison for the grid of interrupted images where a hand rises from a mountain amid the fragments of previous pages: the top of a garment, the bottom of a leaf. This interactive, ludic quality, where text-image relationships are activated by the reader, is central to The Usual Arteries’ achievement.

In this regard, the book’s production value is well matched to its form and content. The format maintains a connection between the artist’s process and the reader’s action, which is essentially unfolding the book back into a press sheet. This playful informality does not come at the expense of craftsmanship. The cut pages seem subtly tapered to fold without catching, and the book is easily retrieved from its simple but sturdy slipcase. Despite this manual labor, Illuminated Press has managed 250 copies and kept the price low enough (a sliding scale from $10–15) to compete with conventional chapbooks and zines, offering a model for accessible opuscula that might expand the readership of artists’ books.

The Usual Arteries is also a successful synthesis of Dorney’s visual and literary practices. Her erasure of Flowers in the Attic may be especially apt given the book’s themes of concealing, revealing, loss, and constraint, but it is not Dorney’s first; her previous books include a redacted treatment of Stephen King’s Pet Sematary and another taken from interviews with Shia LaBeouf. At the same time, The Usual Arteries draws on Dorney’s understanding of materiality and interactivity, which is more evident in her installation art and experimental videos. All erasure poetry blurs the line between reading and writing, but The Usual Arteries makes the reader especially aware of their role in co-producing the experience. As a multidisciplinary artist, Dorney is an accomplished bookmaker who also knows when a project is better suited to a different medium; she only makes books that need to be books. And The Usual Arteries, with its economy of text and image, fine-tuned pacing, and balance of simplicity and interactivity, also shows how much Dorney has learned from those other allied arts.

Leave a comment