Warten

Constanze Kreiser

2021

20 pages

8.25 × 5.75 in. closed

Pamphlet stitch

Digital printing with graphite and cut-out embellishments

Varied edition of 20 copies

Warten is a book about waiting for a book about waiting. Constanze Kreiser created Warten (“waiting” in German) while waiting for a copy of Maurice Blanchot’s Awaiting Oblivion to arrive at a local bookstore. Created in 2021, Warten is also about Covid-19. The wait for Blanchot’s book, and the making of Warten in the meantime, are therefore only interruptions in a longer wait. In Blanchot’s book, two unnamed characters find themselves in a hotel room, trying to remember what brought them there. Their attempts to recall their first meeting instead show the limits of memory and the power of imagination to construct reality — and therefore to reveal reality as constructed. Warten is Kreiser’s version of Blanchot’s hotel room: a liminal space we temporarily inhabit, a space where the greatest presence is an absence.

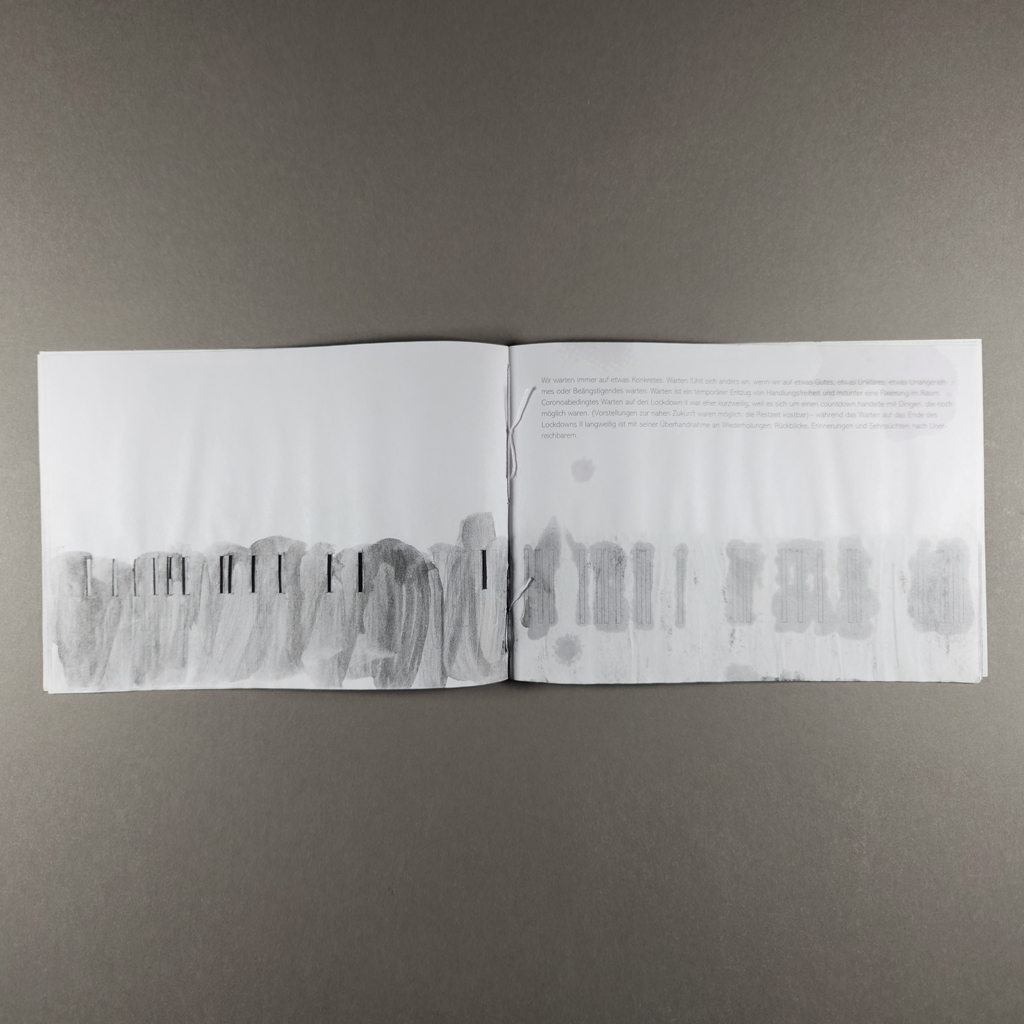

Of course, Warten does not literally represent a hotel room, but the twenty-page pamphlet contains more space and time than its slim proportions suggest. Kreiser produced the book in a variable edition of twenty copies, but the size, page count and text (written in German) are constant. My review copy is embellished with graphite and hand-cut rectangles. Other copies are stained and burned and have pages slit into horizontal flaps. These insistently handmade interventions contrast with the stark, minimalist quality of the printed book.

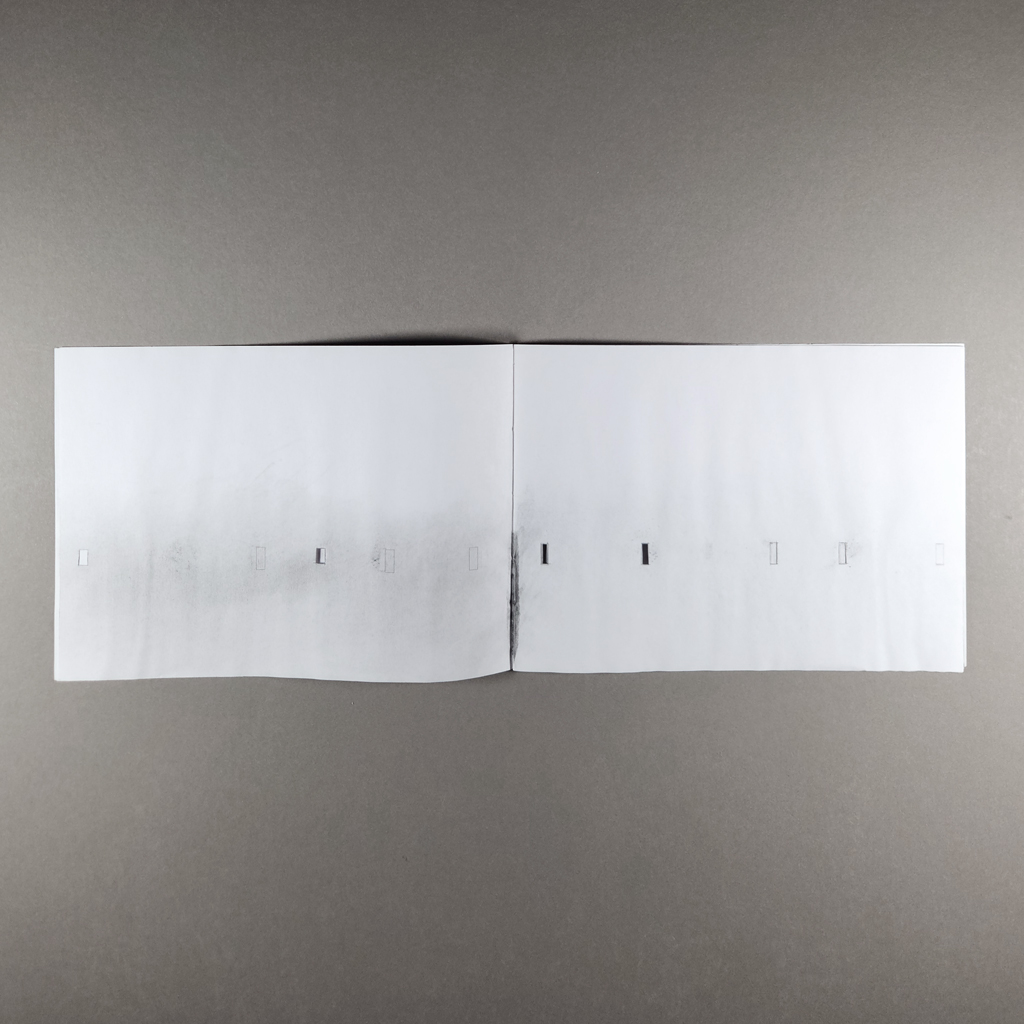

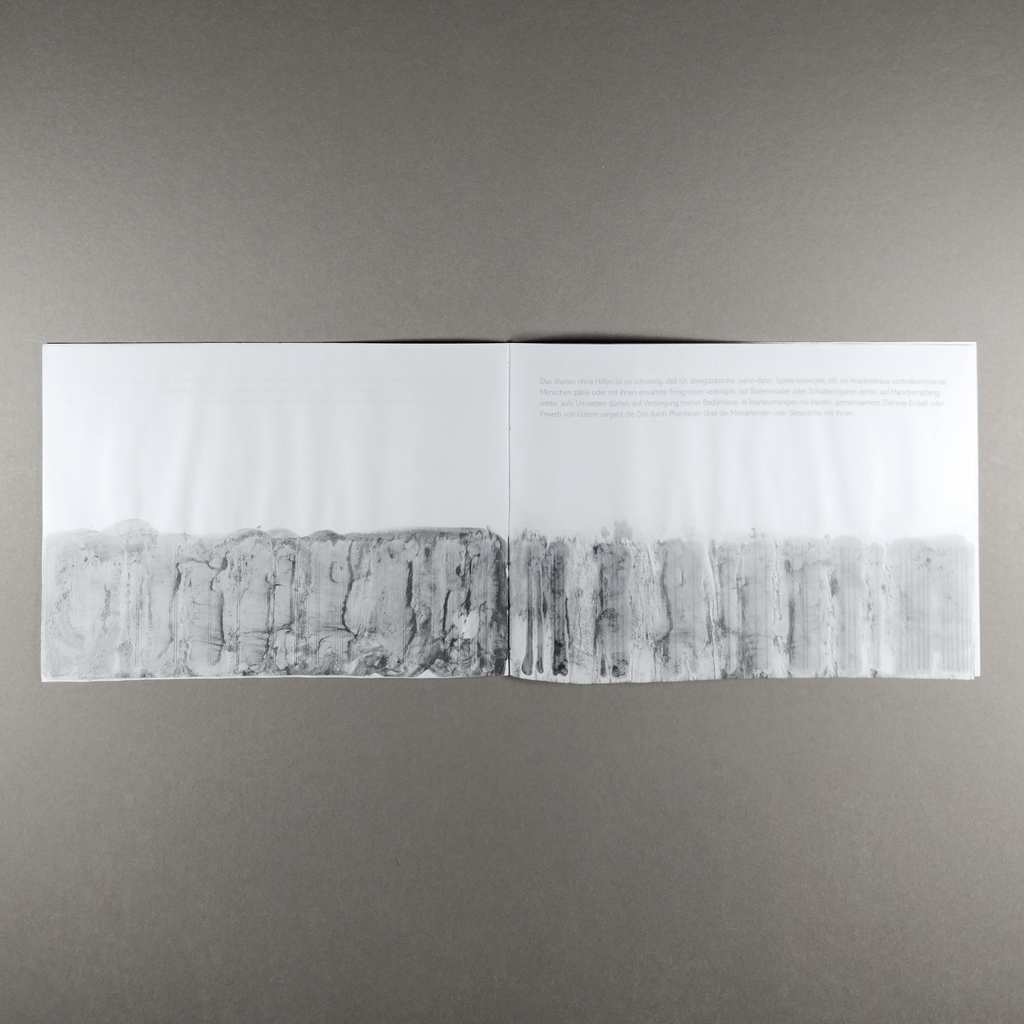

Beneath the cutting and staining, the book’s spare pages present conventional paragraphs of text set in a thin sans-serif typeface. Below these are abstract illustrations, each one an orderly sequence of rectangles. Text and image remain separated by whitespace which dominates the composition. As the book progresses, the rectangles stretch. They begin as short windows, turn into narrow slits, and finally collapse into vertical lines. They also increase in frequency, from one or two per page into sequences that resemble barcodes.

If the imagery therefore suggests some sort of progress, the text rejects any such notion. Each paragraph is a reflection on waiting. Some are quoted from Blanchot, and others are written by Kreiser, but none of them go anywhere or resolve anything. They look back in reflection or forward in anticipation but ultimately circle the absence at the center of the book, as if orbiting the gravitational pull of a black hole. Whereas Blanchot’s protagonists confront their differing realities through dialogue, Kreiser tells the reader directly how she feels and why. Nevertheless, writing amid a coronavirus lockdown, she can come to no conclusions. In Blanchot’s terms, she is writing within the disaster, not aboutthe disaster.

In this context, it is worth reexamining the images, especially the cut-out rectangles. These windows let the reader look through the recto to the next page, but they also keep the previous page in view on the verso. Like memory and anticipation, the cut-outs disrupt the book’s linear progression by reopening the past as the reader moves toward the future. Or maybe we are meant to look at the absences, not through them. Only toward the end of the sequence, when Kreiser’s graphite embellishments are applied loosely in a liquid medium, do the cut-outs reveal anything but whitespace, and then only a murky gray wash.

Warten enacts the experience of waiting that Kreiser describes. We hurry, then linger. We focus, then let our minds wander. We see patterns where there is noise — or nothing at all. We count and measure. We predict, desire, and forget. What is remarkable about Warten is not so much that we find meaning where there is none, but that we can do so even while reading about it.Kreiser is like a magician who explains her illusion and still fools the audience.

Warten also enacts the experience of not waiting. After all, the book exists because Kreiser could wait no longer for her copy of Awaiting Oblivion to arrive. It exists because, as Kreiser puts it, “the enforced immobility of waiting turns into an urge for action.” There is indeed a sense of urgency in the cutting, burning, and staining that distinguish each copy of the book. Repetition and failure are recurring themes in Kreiser’s work, and it is hard not to see the varied edition of Warten as a structure for Kreiser to work through the pandemic, to write the disaster. It would be too literal to invoke Lacan’s description of jouissance as a stain, but Warten exemplifies the paradoxical painful-pleasure that comes with repeated attempts — and failures — to find satisfaction.

Leave a comment