Jericho’s Daughter

Warren Lehrer and Sharon Horvath

EarSay

2024

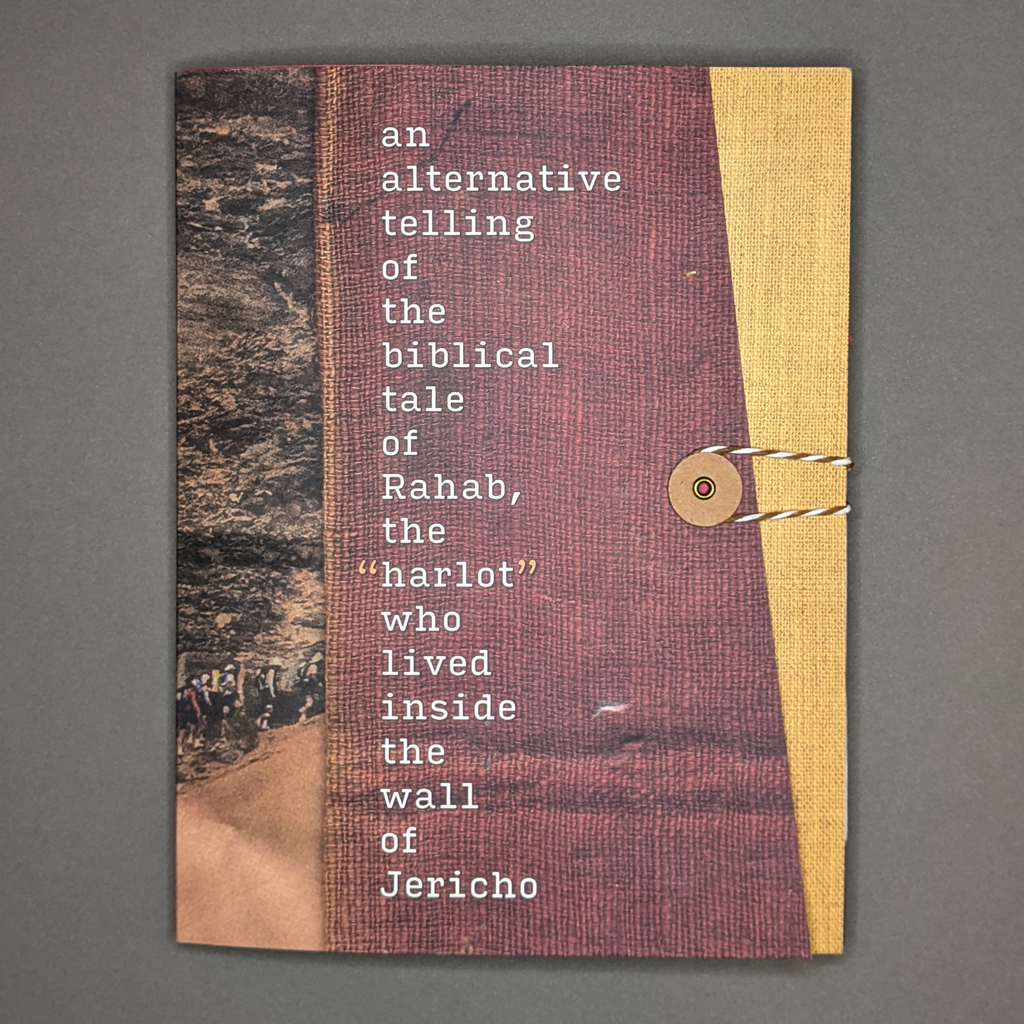

6.75 × 9 in. closed

50 pages

Softcover dos-á-dos with wraparound cover and string and button enclosure

HP Indigo

Jericho’s Daughter reimagines the biblical story of Jericho, this time told from the perspective of Rahab, the Canaanite prostitute who is spared by Joshua when the Israelites raze Jericho and who, having converted and married an Israelite, becomes an important Jewish matriarch. As a work of visual literature, Jericho’s Daughter epitomizes Warren Lehrer’s style, which is partly to say it generously accommodates the aesthetic of his collaborator, Sharon Horvath, whose mixed-media collages and assemblages contribute much of the book’s visual appeal. The book’s structure is a dos-á-dos, which compartmentalizes two storytelling strategies. The first side is a linear, narrative retelling of the usual story in a wry voice. The second side imagines what came next through “found” fragments: excerpts from Rahab’s diary (by Lehrer) and Horvath’s unclassifiable art (simultaneously image and object, figurative and abstract). Jericho’s Daughter is not a facsimile of Rahab’s diary, but with its string and button closure, the slim paperback feels more like reading a diary than a bible.

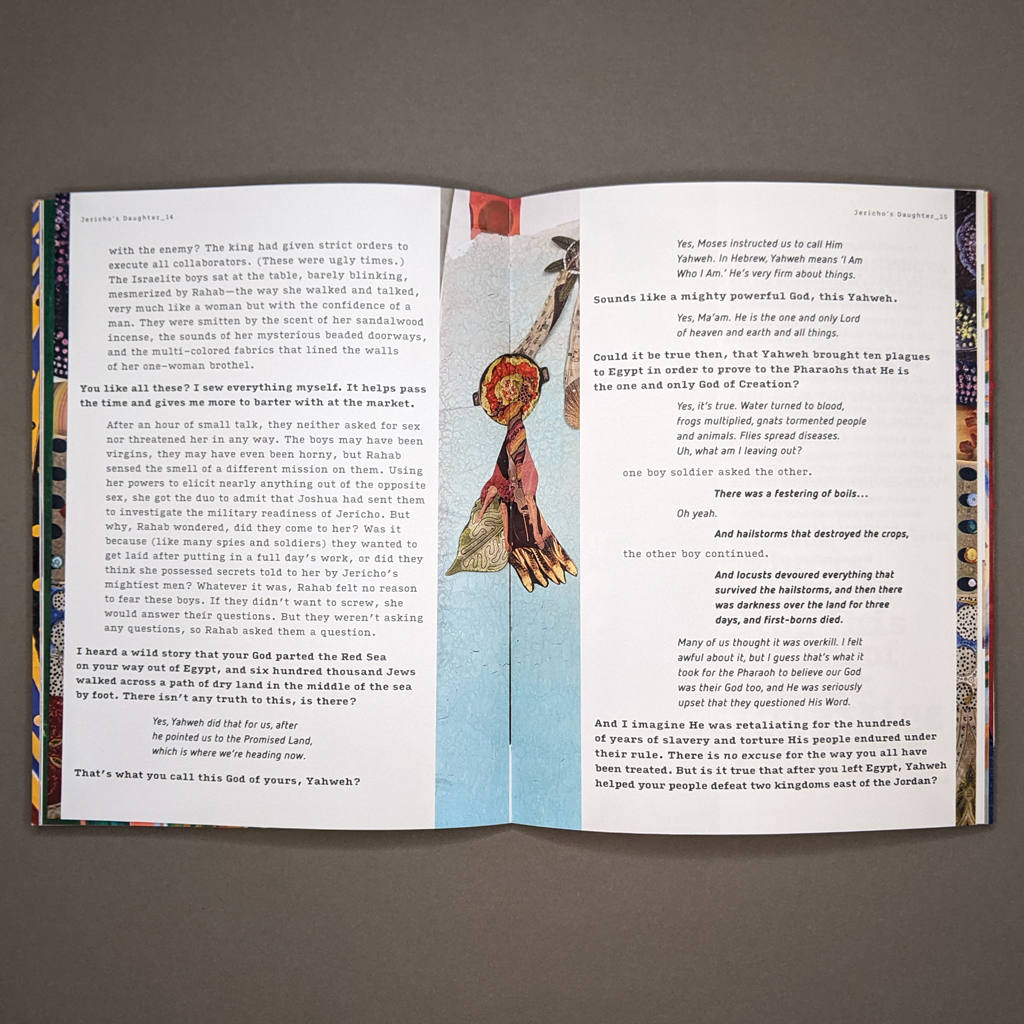

Though the book can be read in one sitting, the experience is surprisingly immersive. Instead of sequestering the publication’s technical details to a colophon or insert, Lehrer integrates the front matter into a filmic sequence of title pages that ease the reader into the visual environment. Furthering the immersive quality, the first side of the book slips seamlessly between narrative and dialogue without character names or even quotation marks. The book is not a script; it is a complete work of visual literature, and the reading is the performance. Each character is identified by typeface, the size and style of which also express qualities of their speech, but the typography is understated compared to other works by Lehrer, especially his visualizations of poetry.

The toned-down typography makes the book’s imagery even more vibrant. Fortunately, the high-quality HP Indigo printing conveys much of the texture in Horvath’s work, which mixes materials like sand and ash with paint and ceramic. The materiality of the images, which literally frame the written dialogue, brings to life the setting where much of the narrative plays out — Rahab’s home, which the narrator tells us is lined with colorful fabrics and permeated with incense. Or perhaps the setting is Rahab’s mind, where the vivid but fragmented imagery evokes memory.

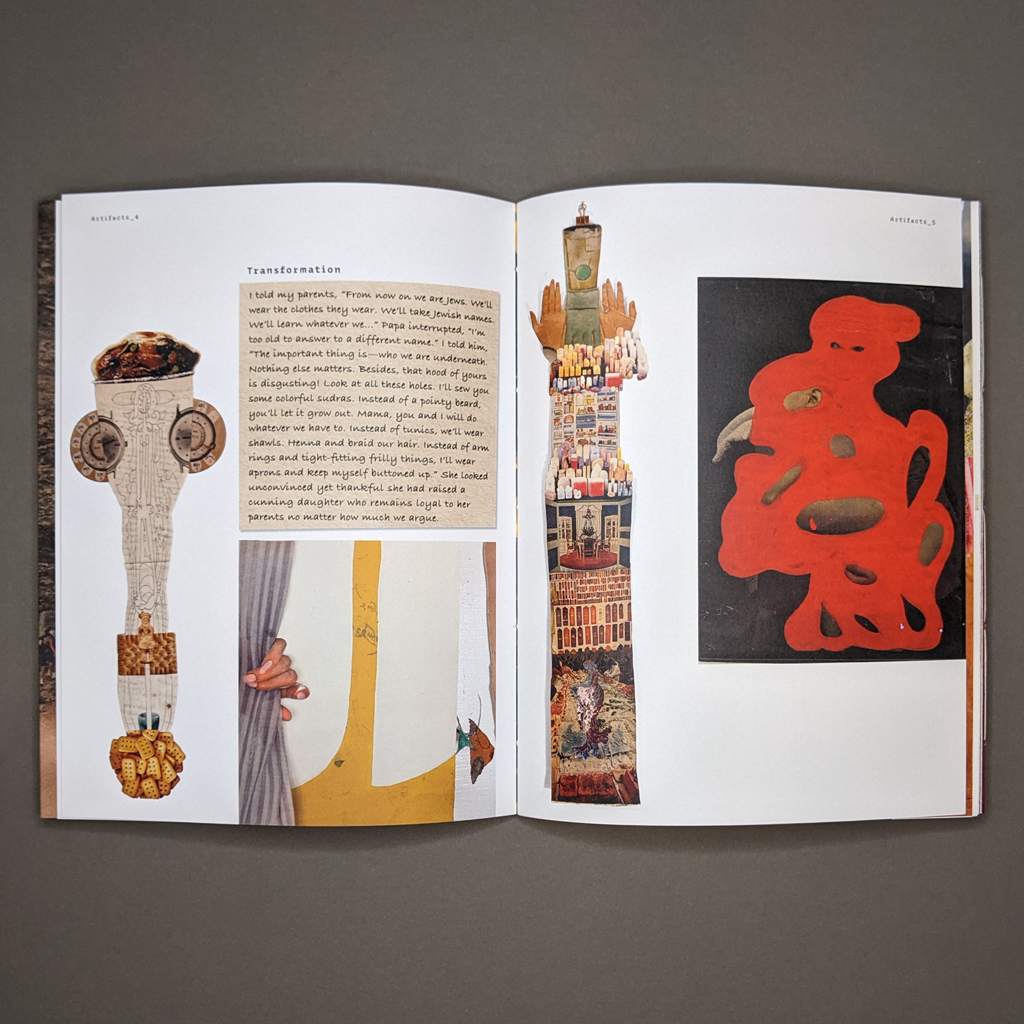

Some of Horvath’s works are presented in full, but many pages are adorned with fragmented close-ups. Like the book itself then, the imagery is both archival (pieced together from fragments) and narrative. Horvath’s sculptural works, cut out and arrayed in the white space of the margins, look like archaeological finds in a museum case or catalogue. Her collages, though also assembled from separate objects, have a more integrated, narrative quality. In an interesting chiasmus, the continuous collages predominate in the book’s diary section, where the text is fragmentary and archival, whereas the individuated, archaeological objects are mostly in the book’s more linear, narrative section. Text and image reinforce one another through complementary strategies.

Lehrer’s handling of the narrator and protagonist also helps ease the reader into the narrative. With plainspoken prose in short sentences and plenty of dialogue, the voice recalls a children’s bible (Haggadah, etc.) even as the text offers frank descriptions of Rahab’s life as a sex worker. The narrator also blurs biblical time with the present day, as though the story could be contemporary. References to pants cuffs mingle with tunics and sudras, and “red alert” with candles and papyrus. The temporalities never completely collapse, but the book strains their separation.

The blurred time periods help Jericho’s Daughter operate allegorically. In Lehrer’s revision, the biblical matriarch is all too relatable. Rahab is inundated with misinformation and fearmongering by elites and disenfranchised from politics. Her dreams of running a textile business are put on hold while she scrapes by with dangerous, demeaning work. She is street-smart, but her horizons are limited. The two Israelite scouts she saves are even less worldly, boys not men, who might nevertheless fit in at the front lines of any armed conflict today.

If the narrative blurs biblical and contemporary time, the dos-á-dos book structure would seem to sharpen such divides. The conventional telling of Rahab’s story indeed follows a two-part structure: before and after conversion, before and after marriage. But the critical revision in Jericho’s Daughter is to refuse such binaries. The book separates the accepted biblical story (side one) from the speculative addition of Rahab’s diary (side two) only to attenuate the difference. In a motif repeated throughout the first side of the book, the narrative text is framed — or forced to the spread’s margins — by Horvath’s organic, ovular forms. Echoing the archived objects that accompany Rahab’s diary in the book’s second half, these forms act as portals or windows that connect the accepted narrative with the revision. The window, of course, plays a key role in the narrative (Rahab saves the Israelite scouts by letting them escape through her window) and is central to a feminist reading of Rahab as a redeemable character whose agency influences the story. It complicates a recurring biblical motif, the “woman in the window,” a liminal, transformational space where women connected to powerful men watch the world but hardly act in it.

As a feminist revision, Jericho’s Daughter goes even further. It is not enough for Rahab’s agency to catalyze her transformation from whore to mother. Rather, the binary itself must be deconstructed. Instead of symbolizing faithful conversion, Rahab’s diary reveals the ambivalence, grief, and trauma — as well as resilience and hope — that one might expect from someone whose entire community was annihilated and who survived by joining the perpetrators. The scenario is unimaginable, yet this revision is more plausible than the biblical version. Jericho’s Daughter therefore complicates the usual truth claims of narrative and archive by pitting the authority of the primary source (Rahab’s fictionalized diary) against the authority of the biblical text (perhaps no less fictional, and endlessly open to interpretation).

Rahab’s plight may be unimaginable, but it is still an effective allegory. After all, war is unimaginable, even if it continues to occur. Incidentally, Jericho’s Daughter was begun before the most recent bloodshed in Israel and Gaza. It deals with millennia-long metanarratives and cycles of violence. That Horvath’s artworks seem simultaneously contemporary and archaic speaks to the universal themes she and Lehrer address.

One of those universal themes, perhaps what resonated most with me, is the unknowability of our parents’ lives. Only Rahab’s diary betrays her true feelings. Outwardly she is the very picture of conversion, marriage, and motherhood. She masks and manipulates with the skills she honed as a “harlot.” But her children are faithful Jews whose offspring include the prophets Jeremiah and Ezekiel. How could they possibly understand what she went through? No child knows their parents as they were before parenthood, but the generational divide is especially poignant for Jews of Lehrer’s generation. Marianne Hirsch coined the term postmemory to describe the experience of the generation whose parents survived a cultural trauma, such as the Holocaust — an experience characterized by memory, but a memory of projection and imagination rather than recollection.

Just as no child can truly understand what their parents went through, no parent can fully protect their child from its effects. By revising the story of Joshua, Jericho’s Daughter offers a better understanding of intergenerational trauma. The surreal juxtapositions and glimpses of narrative that haunt Horvath’s visuals — and rupture the firewall between archive and narrative, memory and history — give lie to the tidy two-part narrative we have inherited. This improved model of trauma is badly needed in a world with so much conflict. Would there be fewer wars if the story of Jericho had been told from Rahab’s perspective instead of Joshua’s? Perhaps that is wishful thinking, but surely we can treat survivors and refugees and disenfranchised people everywhere with greater empathy.

Leave a comment