Prisoners’ Inventions

Angelo

Temporary Services (Brett Bloom and Marc Fischer)

Edited by Mairead Case and designed by Partner & Partners

Half Letter Press

2020

8.5 × 5.5 in. closed

200 pages

Perfect-bound softcover

Digital printing

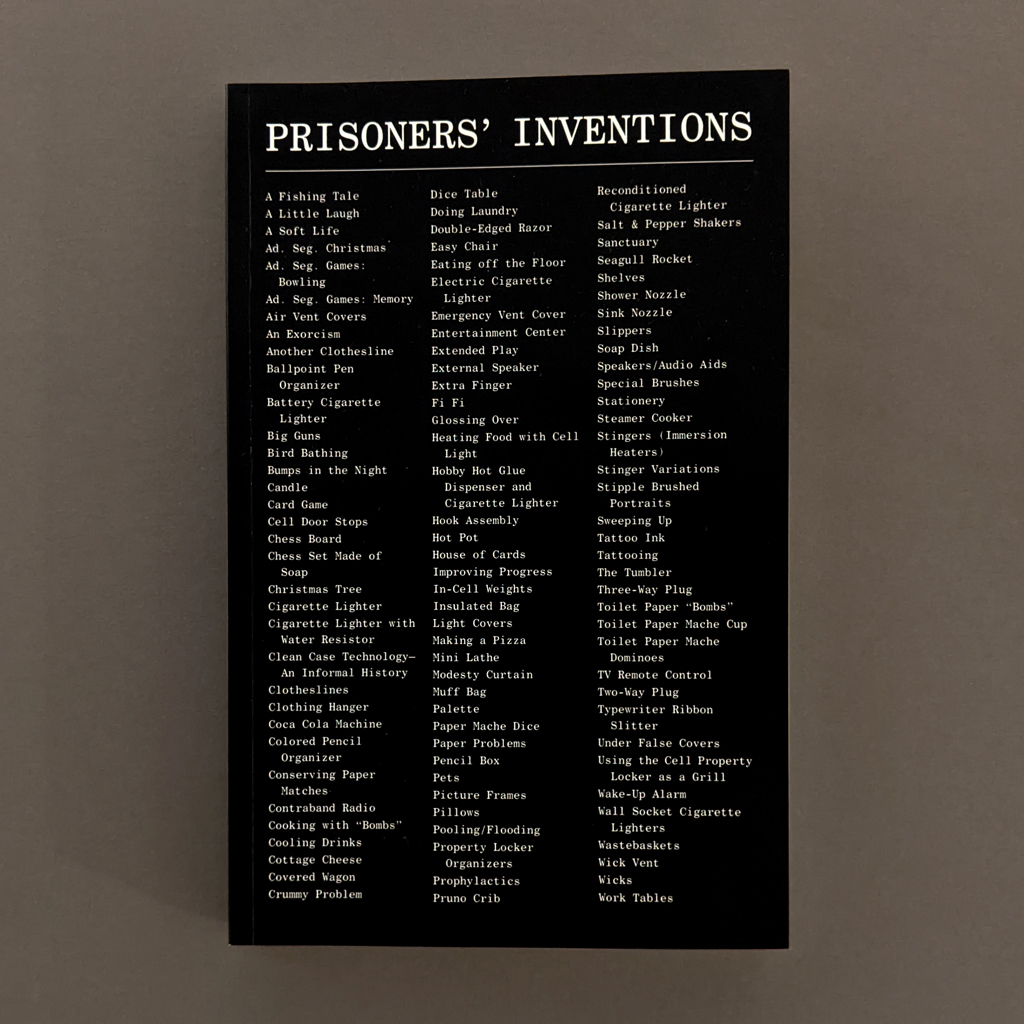

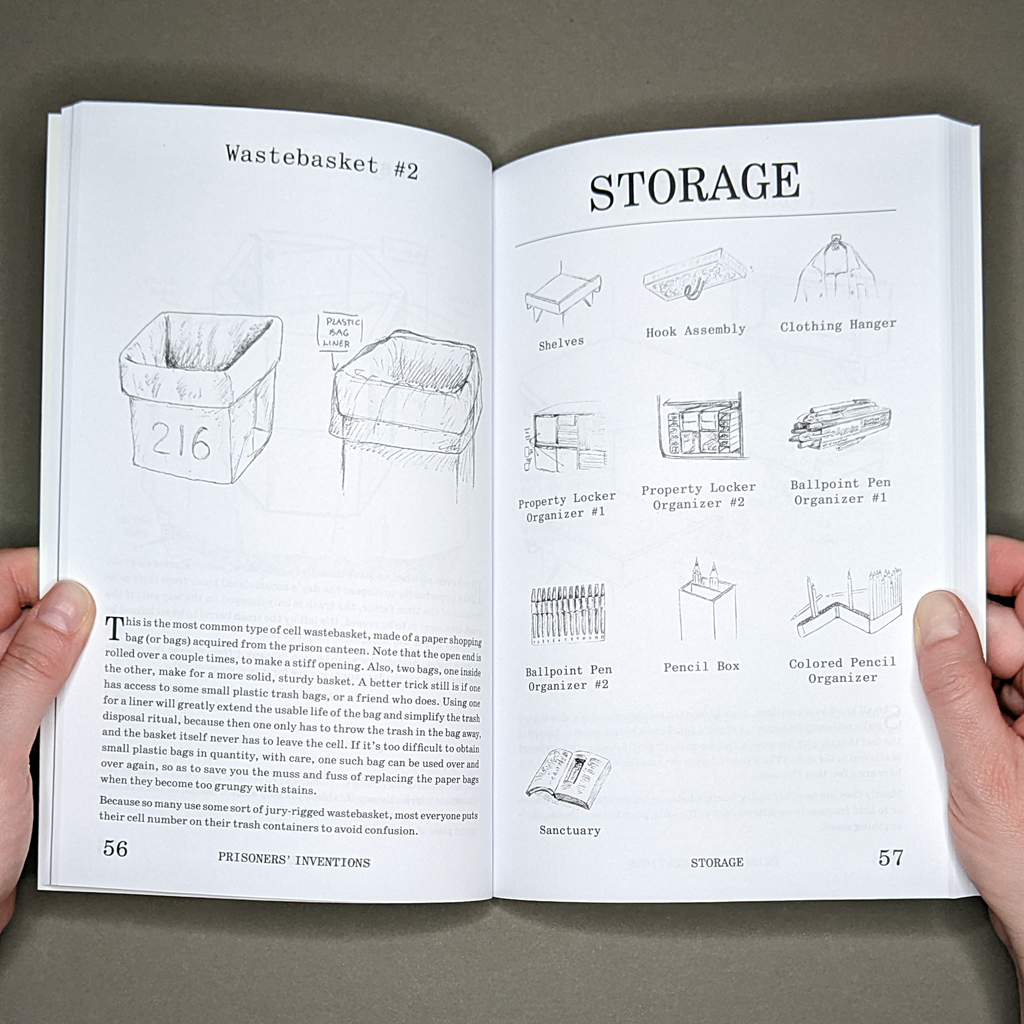

Prisoners’ Inventions is what the title suggests: a compendium of devices designed, built, and used by people incarcerated in US prisons. First published in 2003 with WhiteWalls, this 2020 edition is significantly expanded from its original 132 pages, and has just been reprinted (with minor edits) in 2024. The project’s full history is helpfully detailed in a foreword by Temporary Services. There is also an introduction by Temporary Services’ collaborator, Angelo, who was then incarcerated in California. It is Angelo who provides the prisoners’ inventions, which he renders in extraordinarily detailed ball point pen drawings and lively prose. Some of the texts are short and instructional, but more often Angelo pairs his drawings with a one- or two-page narrative. The inventions are categorized (storage, cooking, etc.) inside the book, but presented in a single alphabetized list on the front cover. With its uneven mix of prison slang, household objects, and familiar words made strange by their context, the cover effectively previews the reading experience.

Angelo is not only the author and illustrator but also the one who aggregates the inventions. Most are things he has used (and often things he has made), but a few have only been described to him by other inmates. In either case, Angelo emphasizes the way knowledge is shared among incarcerated individuals. He is quick to credit a cellmate who taught him a particular technique or namecheck an inmate whose handiwork was renowned. In other words, oral tradition and storytelling are at the heart of this paper book of printed text and image. Though less visible, written correspondence is also a constant presence. Indeed, one could argue the entire project is a work of mail art since the collaboration unfolded (without state permission) via post.

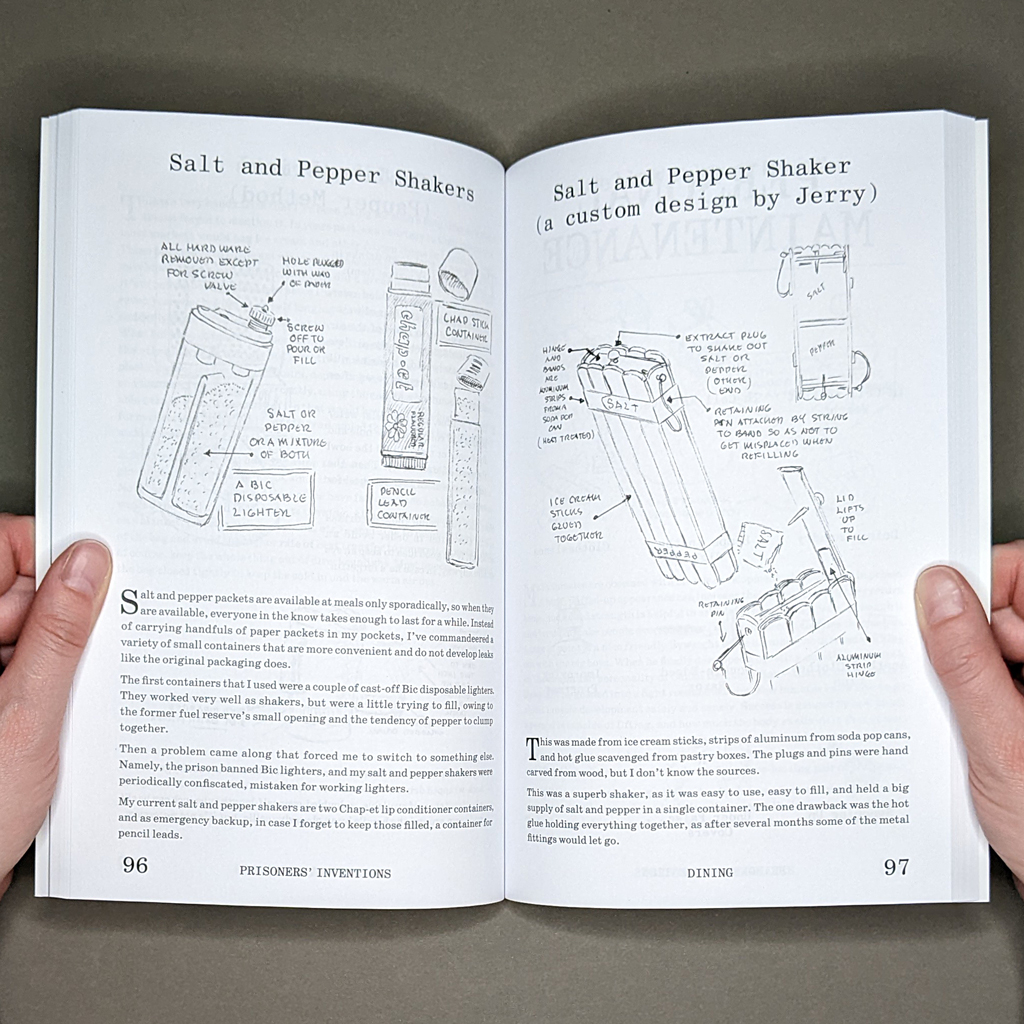

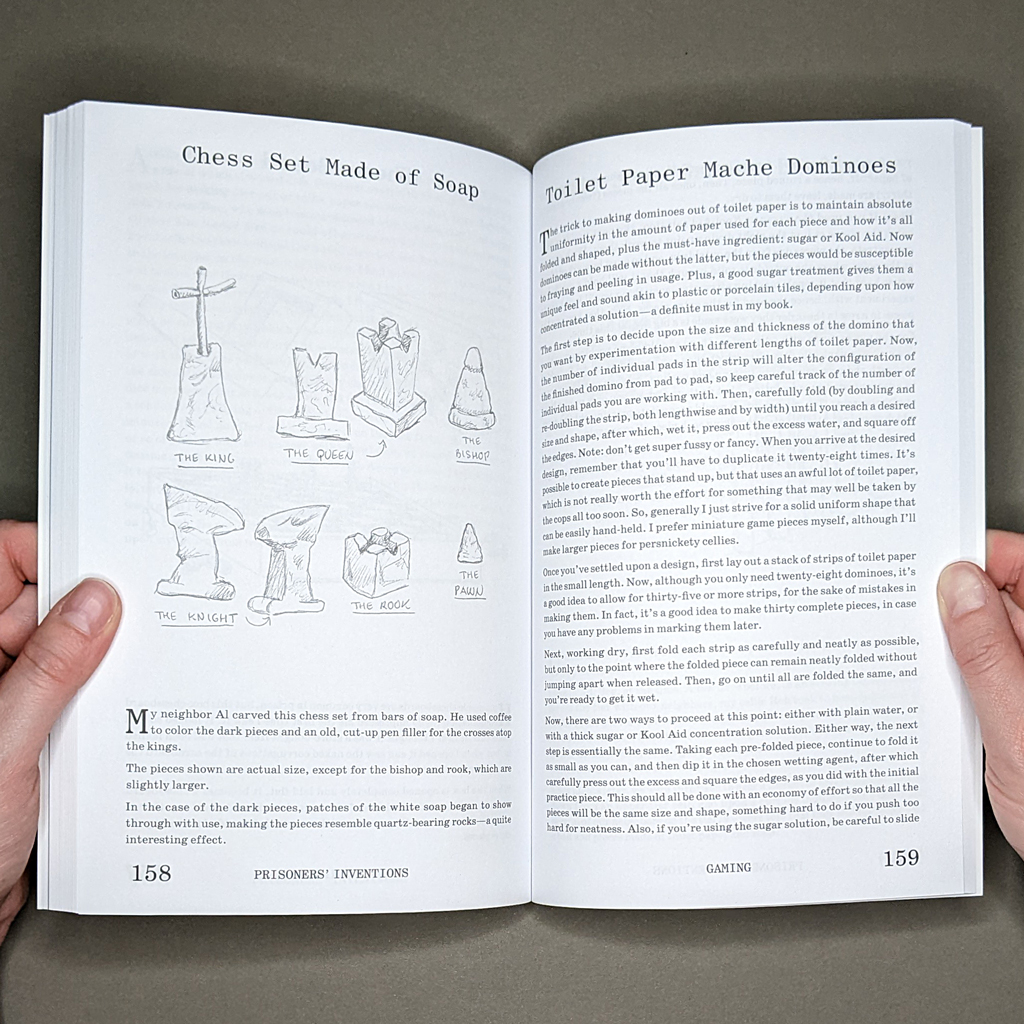

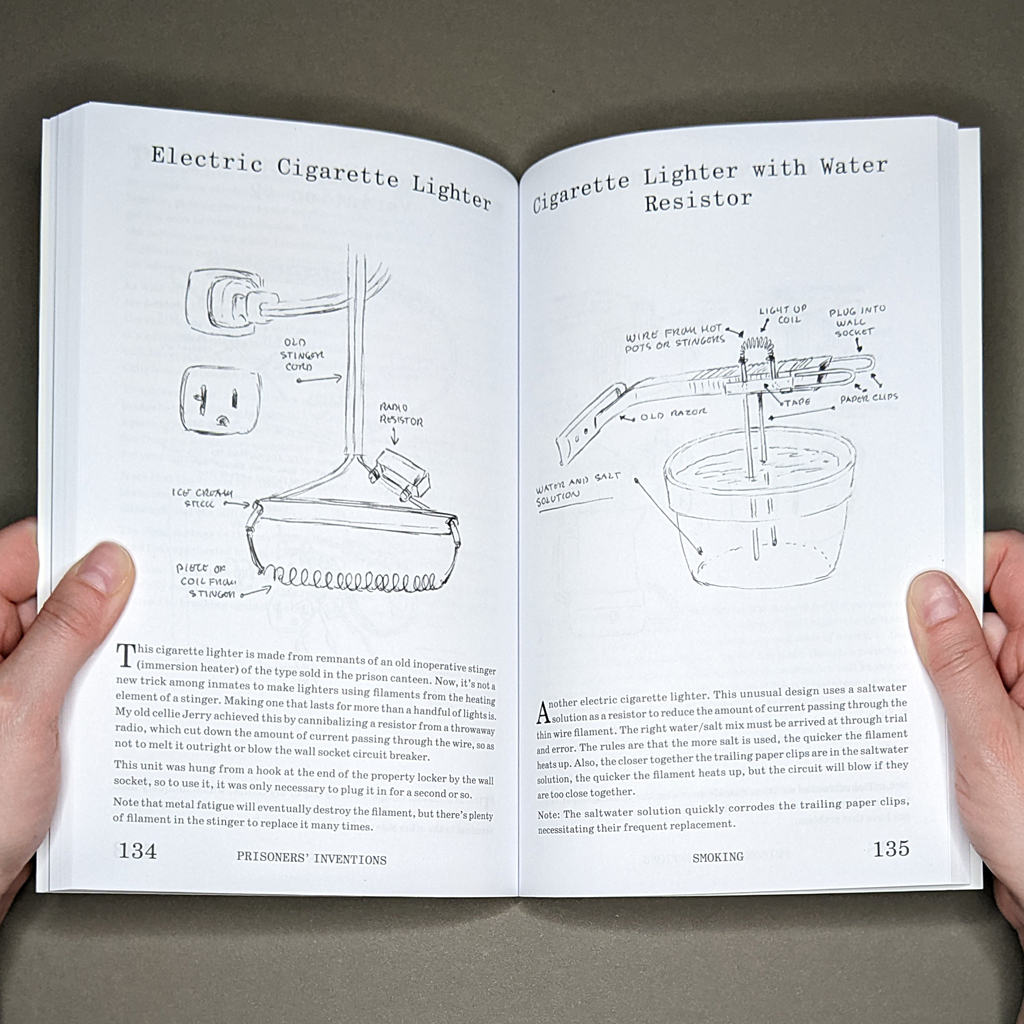

The mutual dependence of text and image, and the combination of straightforward instructions with personal anecdotes, reminded me of my conversation with Chantal Zakari about her own book with incarcerated collaborators, Pictures From the Outside. No matter how evocative, each medium is ultimately inadequate on its own. Even if Angelo’s drawings can explain how an invention might be used, they cannot capture its lore. In fact, what the drawings can and can’t convey drives the reader’s experience (at least the reader who has limited first-hand experience with such inventions). On the one hand, ball point pen enables Angelo’s meticulous detail, which gives a sense of scale, mechanics, and ergonomics. On the other, the medium gives little sense of material or texture. The result is that the outlines of something might look familiar, only to have its textual description wrench away its relatability. What looks like plastic or metal may be toilet-paper-mache or carved soap.

The tactile experience of such materials will be foreign to many readers, although Angelo admirably describes, for example, the sticky process of working Kool-Aid and toilet paper into a set of dominoes as well as the satisfying clack of the finished pieces. Angelo gives a sense of the time it takes to make things by hand, to painstakingly stockpile materials (and hope they aren’t confiscated), to plan, prototype, and produce. Incarcerated for a quarter century, Angelo presents this sense of time with stubborn equanimity. An inmate creates something, a guard confiscates it, and so the cycle continues. For the reader, though, the inventions — and their fabrication — remain almost incomprehensible, situated as the reader is outside the flow of carceral time, the deprivations of prison, and the whims of corrections officers.

Whether an invention is introduced with a humorous anecdote or an explanation of the hardship that motivated its creation, Angelo’s testimony is moving. But the book is more than a series of vignettes; its structure and presentation contribute to the message. Perhaps the most overt editorial interventions are the categories: home furnishings; storage; cooking; dining; personal maintenance; bathing; smoking; recreation; gaming; arts & crafts; little extras. The categories sound disarmingly domestic, as if taken from a catalogue or lifestyle magazine. They also speak to basic human needs. The gulf between the inside and the outside is made all the more poignant by this shared vocabulary. Unsurprisingly, the inventions fit uneasily into such familiar categories, and that illustrates another of the book’s major themes: the tension between order and chaos. Even the most anodyne invention, including one meant to maintain order — a clothes hanger or pencil organizer — is considered contraband in prison. However, where prison guards struggle to control these inventions, the book logs them in a table of contents, neatly typologized.

This is not to say that the book arrests the inventions’ unruly creativity. For one thing, the reader can use the book as an instruction manual (Temporary Services did just that for the 2003–2004 exhibition Fantastic! at MASS MoCA). Not every reader will make their own dumbbells or cottage cheese, but Prisoners’ Inventions is an instructional manual in another sense: it shows us how to see the small acts of creativity all around us. (In this regard, Prisoners’ Inventions fits perfectly alongside Temporary Service’s Public Phenomena series and Marc Fischer’s Public Collectors series.) In his introduction, Angelo says that, at first, he didn’t think there would be anything interesting to depict. The subsequent outpouring shows what a change in perspective can achieve.

Some of the book’s details, and certainly the characters, situate Prisoners’ Inventions in a particular place and time. As a celebration of innovation, though, it speaks to something more universal. The deeply human urge to solve problems and express oneself accounts for much of the book’s continued relevance, but two decades after its first publishing, we must also acknowledge how little has changed regarding mass incarceration. As I read, I kept wondering what these men — Angelo, Billy, Victor, Randy, Ron, and Little John — might invent in a different system.

Leave a comment