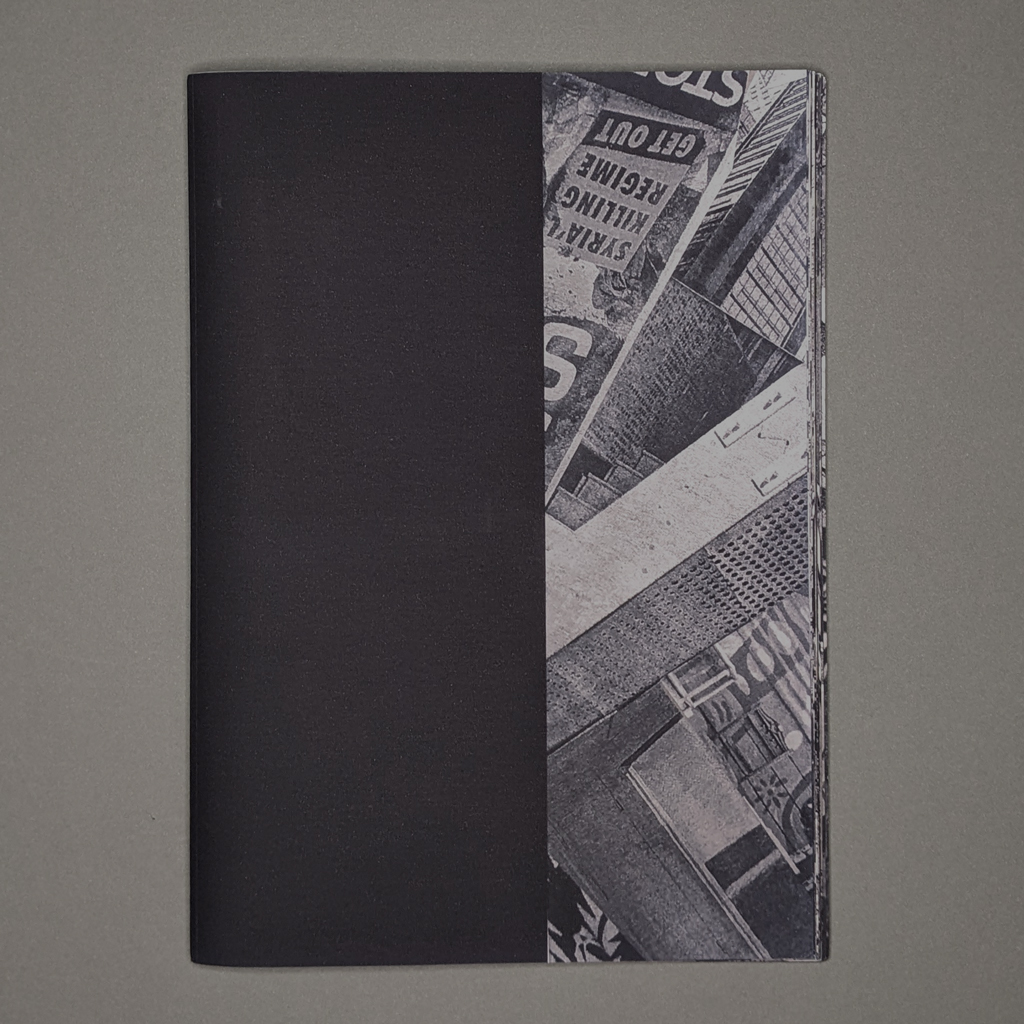

Senza Titolo (Untitled)

Angelo Ricciardi

2021

Unbound; one folded and gathered signature

6 × 8.25 in. closed

48 pages

Ink jet

Edition of 10

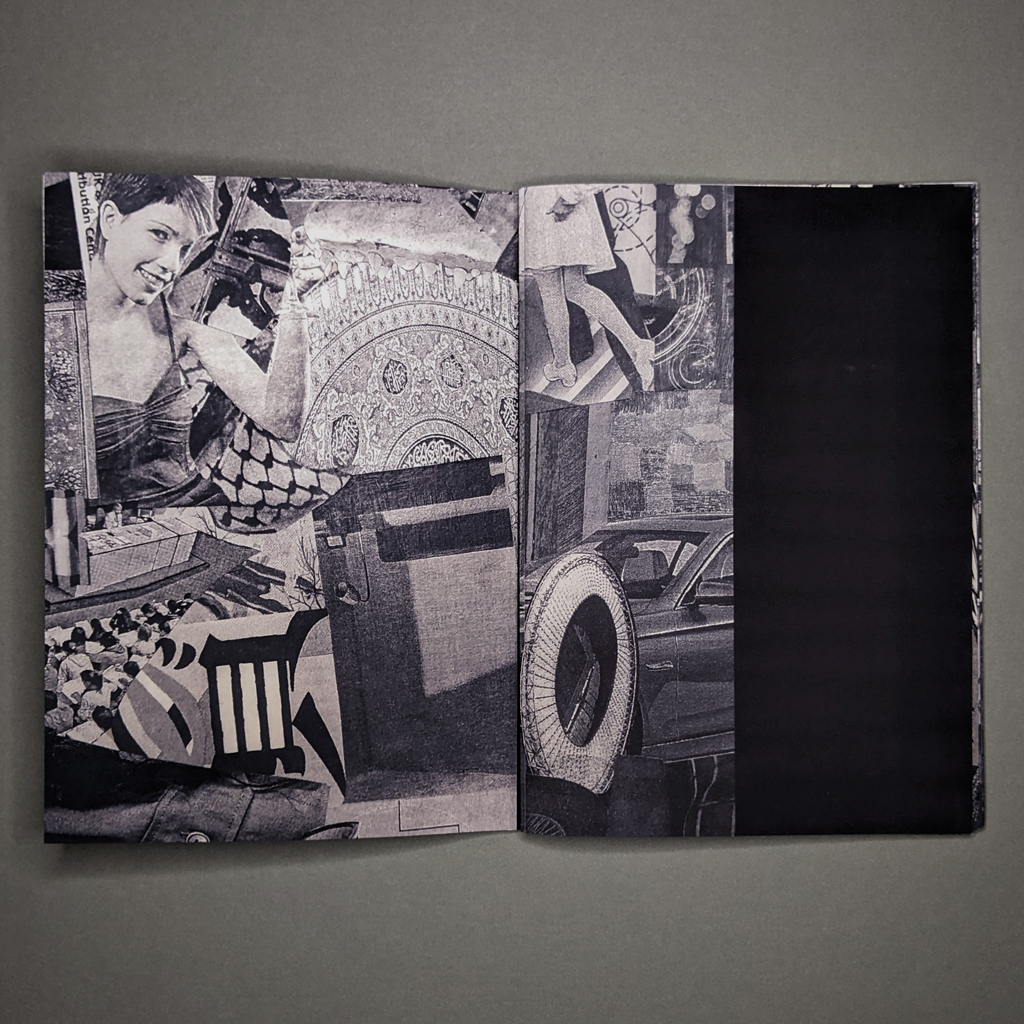

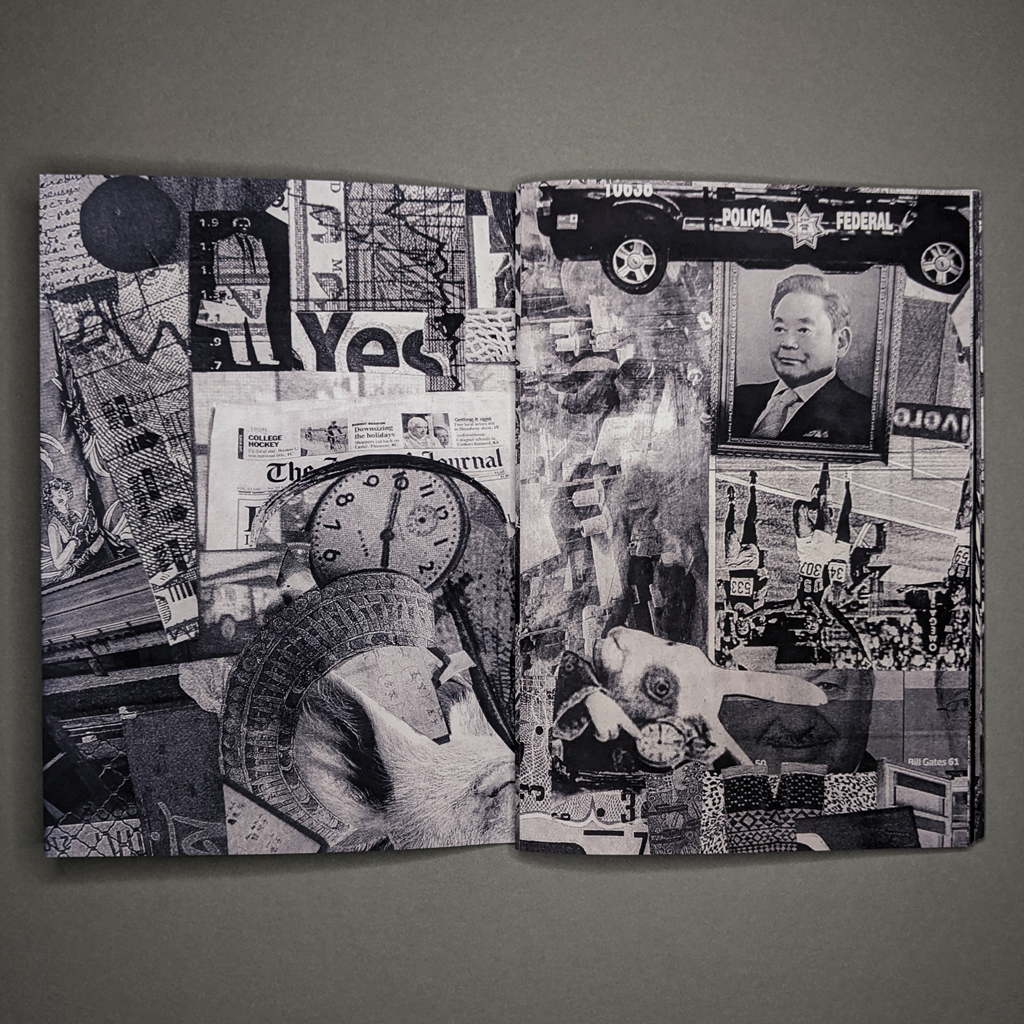

Angelo Ricciardi’s Senza Titolo (Untitled) is a busy book of fragmented collages, printed full-bleed in black and white. The whites are toned down to a light gray, lending the book the appearance of newsprint. And, like a newspaper, the book’s 48 pages are folded and gathered but left unbound. Ricciardi shares his longstanding interest in newspapers with many collage artists, and Senza Titolo recalls avant-garde movements of the early twentieth century: Cubism, Dada, and Futurism. The collages teem with images but also contain text, and it seems another of Ricciardi’s interests is the interaction of text and image. In Senza Titolo, text and image clash as often as they concur. Amid controlled chaos, the reader must make their own meaning.

The imagery speaks to both tasks: controlling chaos and making meaning. There are police and protestors, old master artworks and cartoon characters. The grayscale rendering helps unify these incongruous images, itself a trade-off between information and order. Furthermore, the relatively low contrast — few bright whites and a full spectrum of grays — slows the reader down as they parse the boundaries of fragmented objects. Their values may be subtle, but the forms are expertly assembled; each page has a strong composition. Ricciardi guides the reader’s eye, and the mind hurries to catch up.

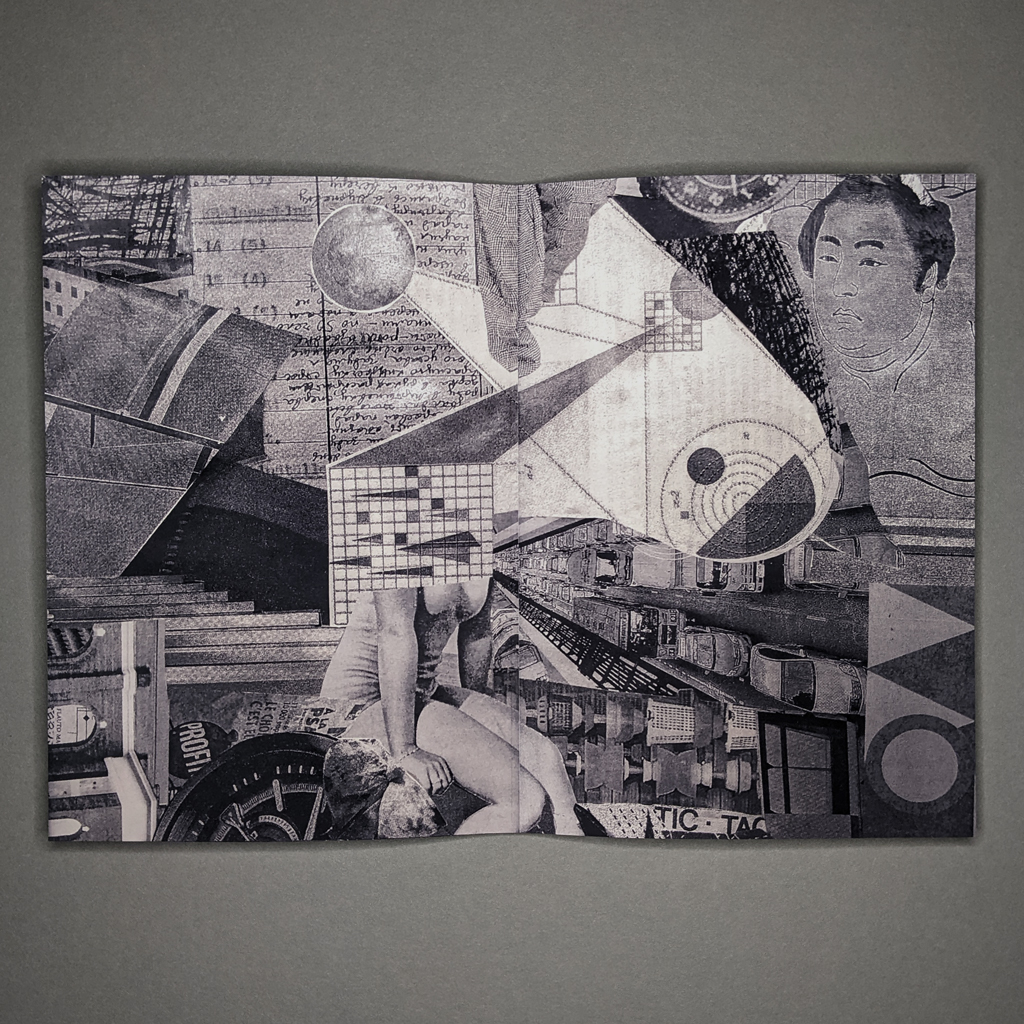

Composition also reveals the structural complexity of Senza Titolo. Each folded sheet has a complete college on each side, but these are only visible if the sheets are removed from the gathered signature. When gathered into a pamphlet, the verso and recto are from different collages. Despite the chaos, the pairings are not entirely random; Ricciardi uses visual devices to call across the gutter. Portraits of people are especially effective in this regard, but the echo of a geometric form is all it takes to connect the composition of the two-page spread. (If, in fact, the paired pages are random, it goes to show how naturally readers seek patterns and construct meaning.) In an unbound book — read as pages, spreads, and sheets — possible meanings multiply, and then multiply further as they accumulate in what is ultimately a time-based experience.

In some ways, composition and time are in conflict. The immersive, all-over design of each collage pulls the reader inward instead of propelling them to turn the page. Fortunately, this is balanced by the book’s game-like quality, which invites readers to recognize references and decode symbols. Ricciardi introduces a sense of rhythm and pacing by interspersing vertical bands of solid black, which cover half a page and split the book into several sections. Even without obvious themes or through lines, these sections break the book into manageable units for the reader and offer signposts in the absence of page numbers.

The passage — and stoppage — of time is not just a feature of the book’s reading experience but also its content. Clocks and watches appear throughout, and the mash-up of historical references and recent events is another form of temporal play. But while the source images span centuries, Ricciardi’s visual strategies are of a particular moment. There are elements of Dada, particularly Hannah Höch’s political commentary, which is in no way random or resigned. The fragmentation of space and perspective, of course echoes Cubism, which is credited with first incorporating newspaper into art. And there is an overall sense of a decadent present burdened by history, which features in Futurism. In other words, Senza Titolo seems like a work from the turn of the twentieth century. So why does it still succeed?

If the political stakes of collage, montage, and fragmentation have changed since Walter Benjamin theorized them in the 1920s, Ricciardi uses the structure of the book, as well as its content, to reach today’s reader. The unbound book makes tangible the battle between chaos and control: one must physically disorder the book by ungathering its pages to gain visual mastery of the complete compositions. Today’s reader may be less shocked by collage, but order and chaos are as salient now as a hundred years ago, and so is the related search for meaning and purpose. Senza Titolo’s absurd juxtapositions carry on a legacy of nonsense and relativism that stretches from Dada to postmodernism and beyond. And like these precedents, Ricciardi’s message is anything but meaningless.

Leave a comment