NEW YORK POST Flag Profile

Michalis Pichler

2017

Co-published by COLLAGE and “greatest hits,” distributed by Buchhandlung Walther König

Folded, unbound newsprint

88 pages

11 × 14 in. closed

Offset

Edition of 5,000

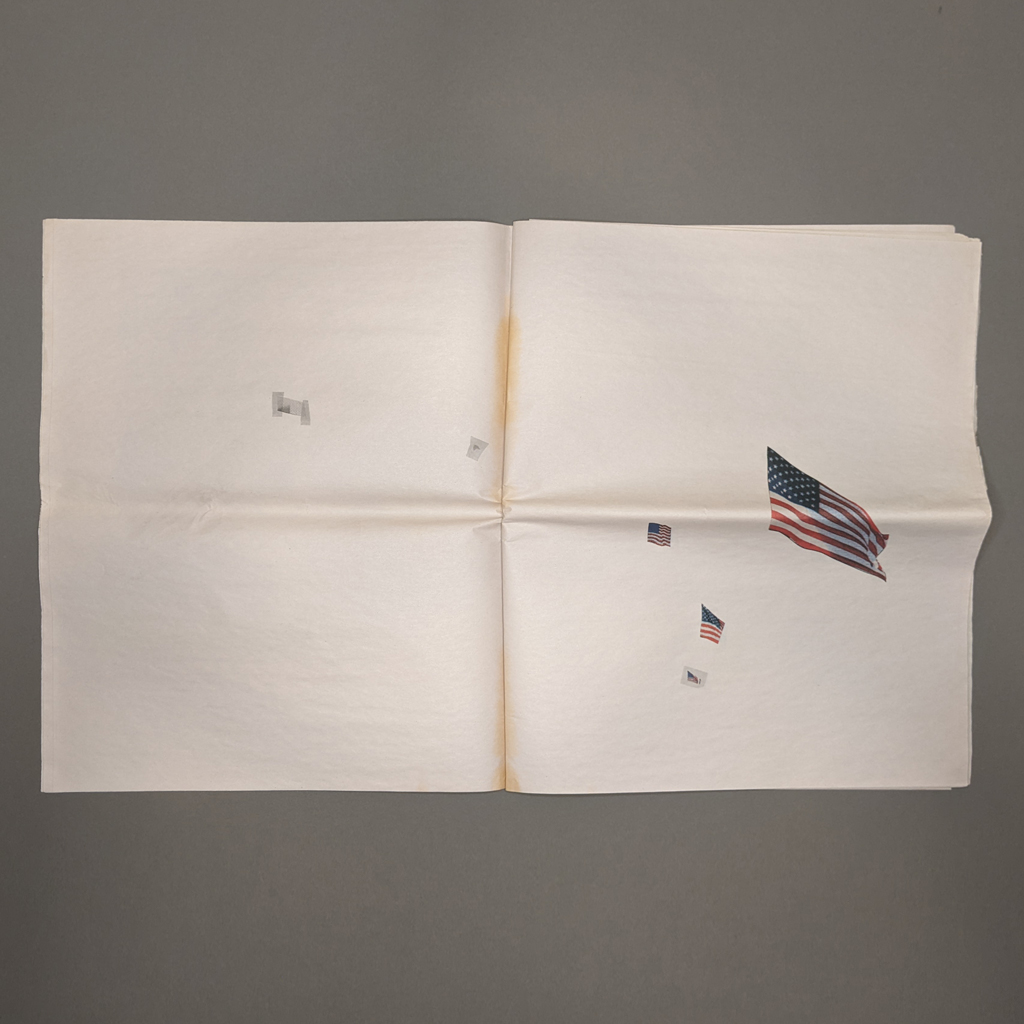

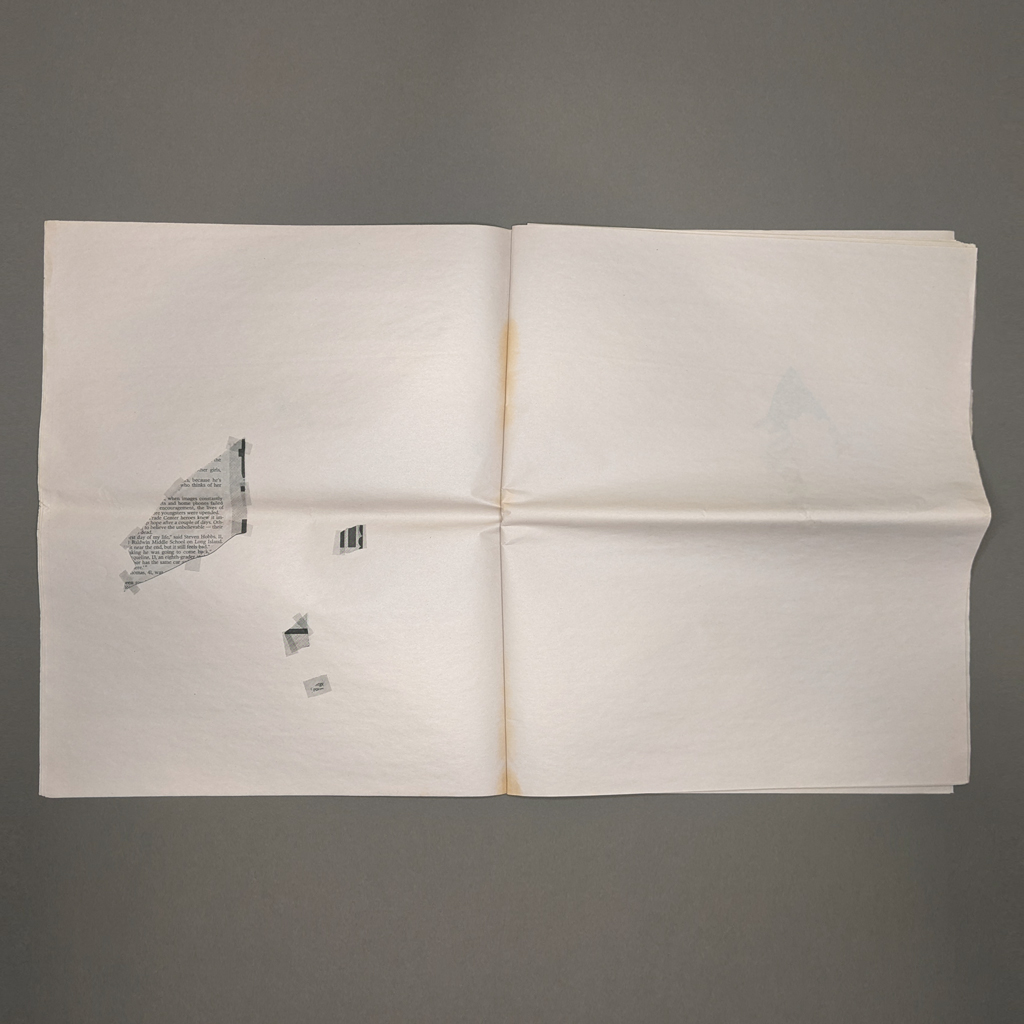

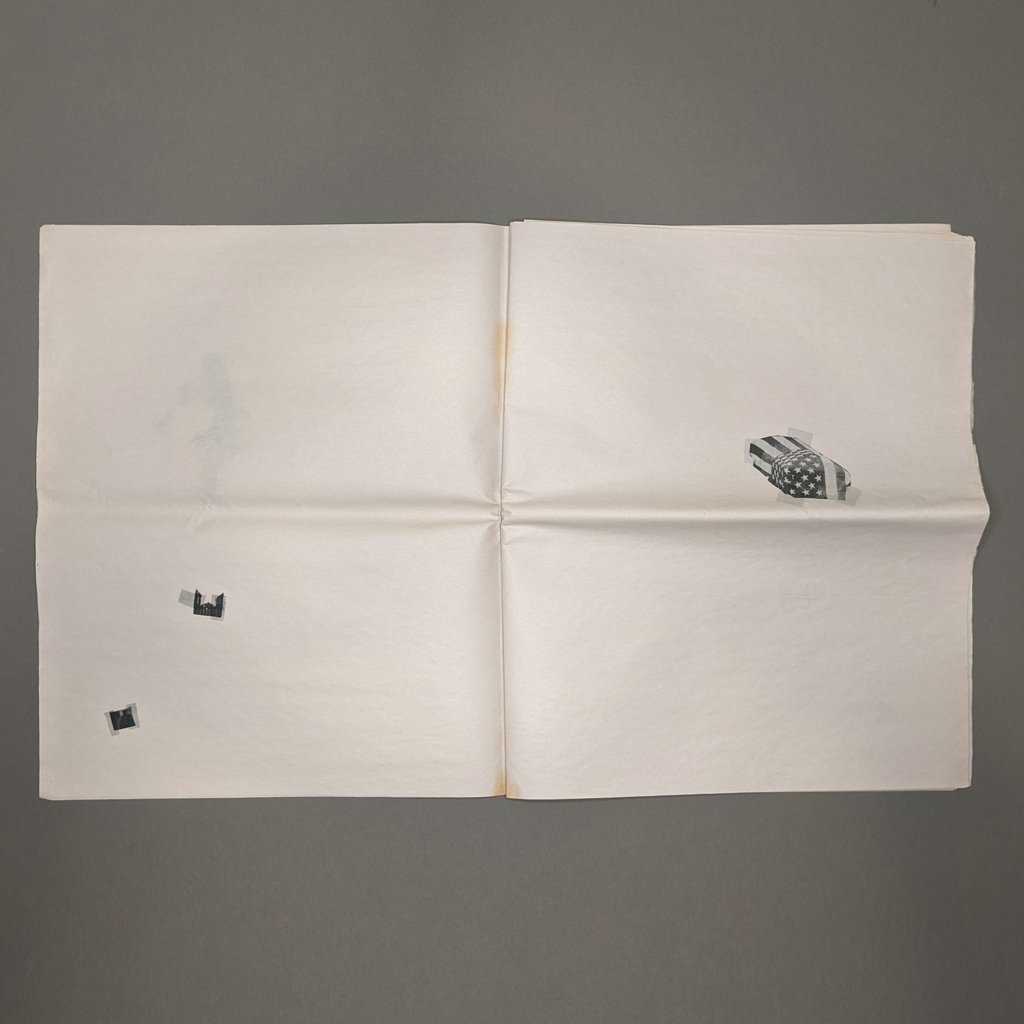

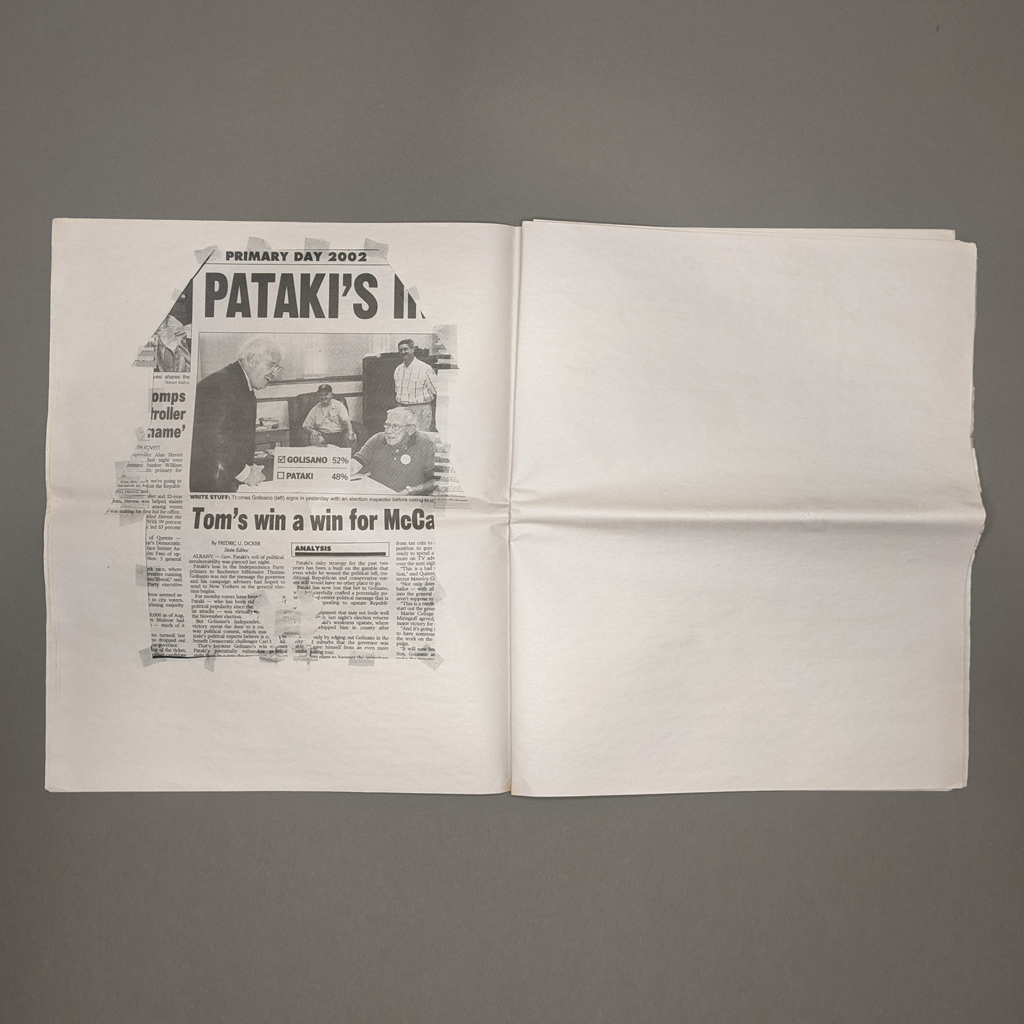

NEW YORK POST Flag Profile is a redacted version of a special edition of the New York Post issued on the first anniversary of the September 11 terror attacks. Specifically, Michalis Pichler has cut out all the American flags from the original issue and essentially pasted, or rather taped, them into a blank newspaper, preserving their precise location and orientation on the page. I say essentially, because there is a pre-press trick: whatever is on the backside of the excised flag is also pasted back into the newspaper in its corresponding position. The result is a new version of the special issue featuring nothing but American flags and whatever happened to be printed behind them. Given the potent symbolism of erasure in the context of loss, of silence in the context of remembrance, and of American flags in the post-9/11 era, NEW YORK POST Flag Profile is a high-stakes exploration of longstanding concerns for artists’ books: how context informs content and how the physical space of the page produces meaning.

The presence of entirely blank pages among NEW YORK POST Flag Profile’s eighty-eight pages suggest that Pichler has faithfully followed the original special issue, except for the centerfold and subsequent page, which serve as a colophon and project statement. The newspaper format enhances the impact of the blank pages, because a reader cannot quickly flip through or skip over them as one might with a book. It also allows for the relatively large edition size of 5,000. The project seems well suited for wide distribution. It can be appreciated at many levels, but its impact is practically immediate, and its construction is largely self-explanatory.

One reason NEW YORK POST Flag Profile succeeds at multiple levels is that it illustrates the importance of context in both concrete and abstract ways. Separated from the surrounding text and image, it is difficult to tell whether the flags belonged to a news story, a commemoration, or an advertisement. The images run the gamut from flag-draped coffins to generic backgrounds behind text that Pichler has painstakingly cut out. Beyond the page, the context of the publication matters, too. Consider the difference between the New York Post, a conservative tabloid, and the New York Times, which Pichler first treated with the same approach in his 2003 New York Times Flag Profile. Furthermore, the meaning of the American flag continued to change between 2002 and 2017. Just as the flag took on new meaning, and ubiquity, after 9/11, so too did it change during the MAGA era of Donald Trump’s first presidency.

Perhaps even on September 11, 2002, when the original newspaper was published and when the United States had invaded Afghanistan but not yet Iraq, the flag meant something different than it would by Pichler’s 2003 publication. NEW YORK POST Flag Profile is not about 9/11 per se but about its commemoration a year later. Pichler retains the original cover and title of the Post’s special issue: “Lest we forget.” The largely empty pages might be seen as a moment of silence, whether out of respect or at a loss for words. Moreover, their creation through erasure might invoke the loss suffered in New York and elsewhere. But Pichler’s erasure is ambivalent; it seems to enact the very forgetting that the Post wants to prevent. Do the flags paper over a more complex discourse with facile patriotism? Does the erasure interrupt the then-inescapable images of airplanes, fireballs, survivors, and victims? The latter phenomenon, the incessant repetition of the same event, was an anomaly for the news media. “Lest we forget,” proclaims the Post, but daily newspapers are in the business of forgetting. History doesn’t sell like novelty, and the new is rarely as outrageous when viewed in context.

Newspapers’ bias towards the present is visible in their ephemerality, and Pichler retains this quality. The yellowing and creasing of my own review copy is a testament, but even a pristine copy bears the marks of Pichler’s paste-up production, most notably the adhesive tape still visible around the edges of many images. By emphasizing the materiality of the page, the tape helps activate the white space that dominates most spreads. This is a major concern for Pichler, who has produced numerous projects related to Stéphane Mallarmé’s Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard, which is seen as a watershed moment in poetry’s recognition of the page. Newspapermen understood this before poets, though, and Pichler interrupts his publication with a four-column tally of square inches dedicated to the stars and stripes in New York Newsday, New York Post, New York Times, and Village Voice anniversary editions.

In newspapers, column inches are a measurement of monetary and cultural value — the space given to a story, a journalist, or an advertiser informs the message as surely as Mallarmé’s typography guides his reader. Important stories go above the fold, and advertisers can pay for premium placement. If Mallarmé reminds us that the page is a presence, not an absence, Pichler reveals the page to be as ideological as it is material. The incidental information that is retained because it is printed on the backside of a flag might be subject to chance, but it is not random. Far from “all the news that’s fit to print,” each page reflects decisions made by editors, publishers, and ad reps.

The importance of editorial choices may be most obvious in Pichler’s quantitative comparison of four very different New York newspapers, but the entire publication resensitizes the reader to the newspaper format, which is so familiar it risks becoming transparent. As a critique of politics and mass media, NEW YORK POST Flag Profile has obvious parallels with tactical media projects like the Yes Men’s New York Times Special Edition (2008), which launched a week after Obama’s first election, full of hopeful yet implausible alternative headlines. However, Pichler looks deeper than content. By thinking with artists’ books, he deconstructs the newspaper format and the politics of commemoration by attending the interplay between materiality, structure, content, and context. With a print run of 5,000, accessible subject matter, and familiar format, NEW YORK POST Flag Profile introduces these considerations for readers not already steeped in artists’ books. For readers who already think in the language of artists’ books, there is plenty to enjoy in the publication’s visual surprises, semiotic play, and poignancy.

Leave a comment