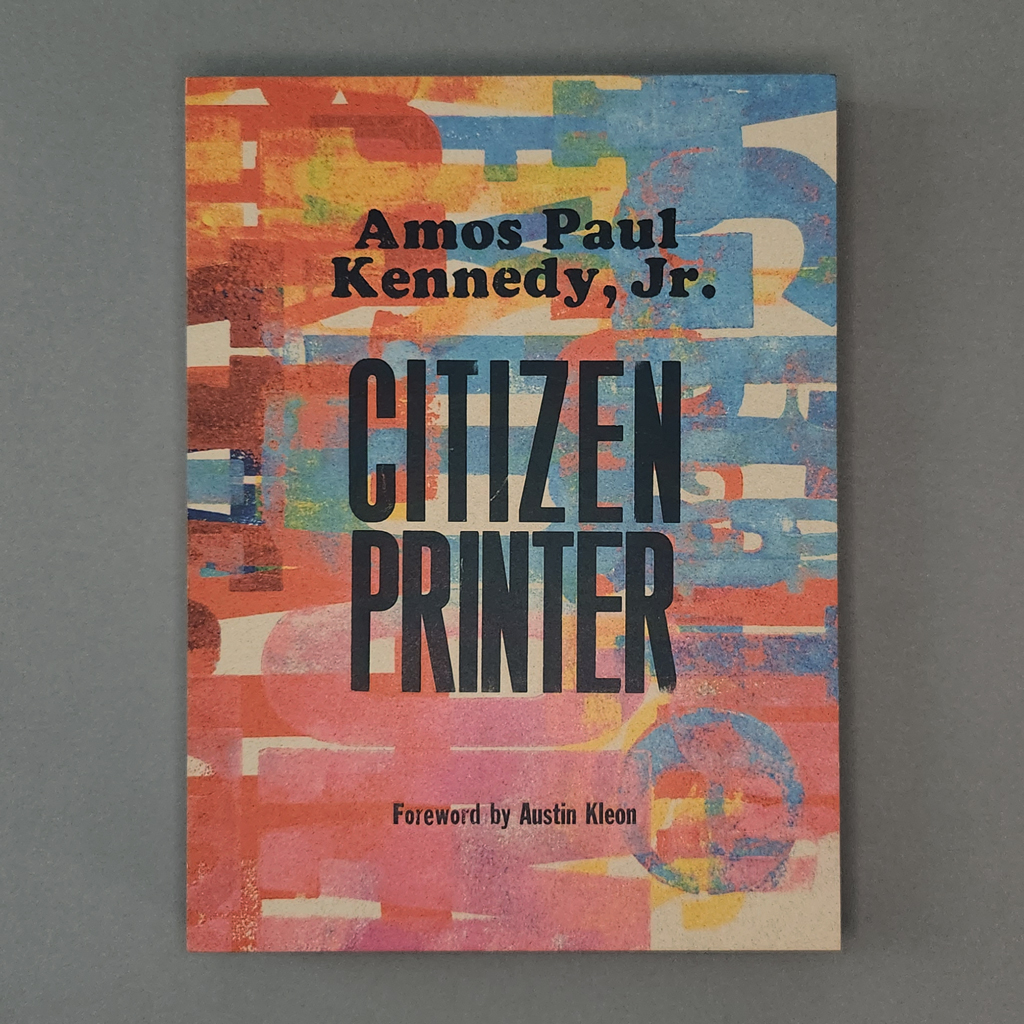

Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr.: Citizen Printer

Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr.

Design by Gail Anderson and Joe Newton

Photography by Aundre Larrow

Foreword by Austin Kleon and essays by Myron M. Beasley and Kelly Walters

Letterform Archive

2024

Smyth-sewn hardcover with exposed spine

292 pages

9 × 12 in. closed

Offset printing

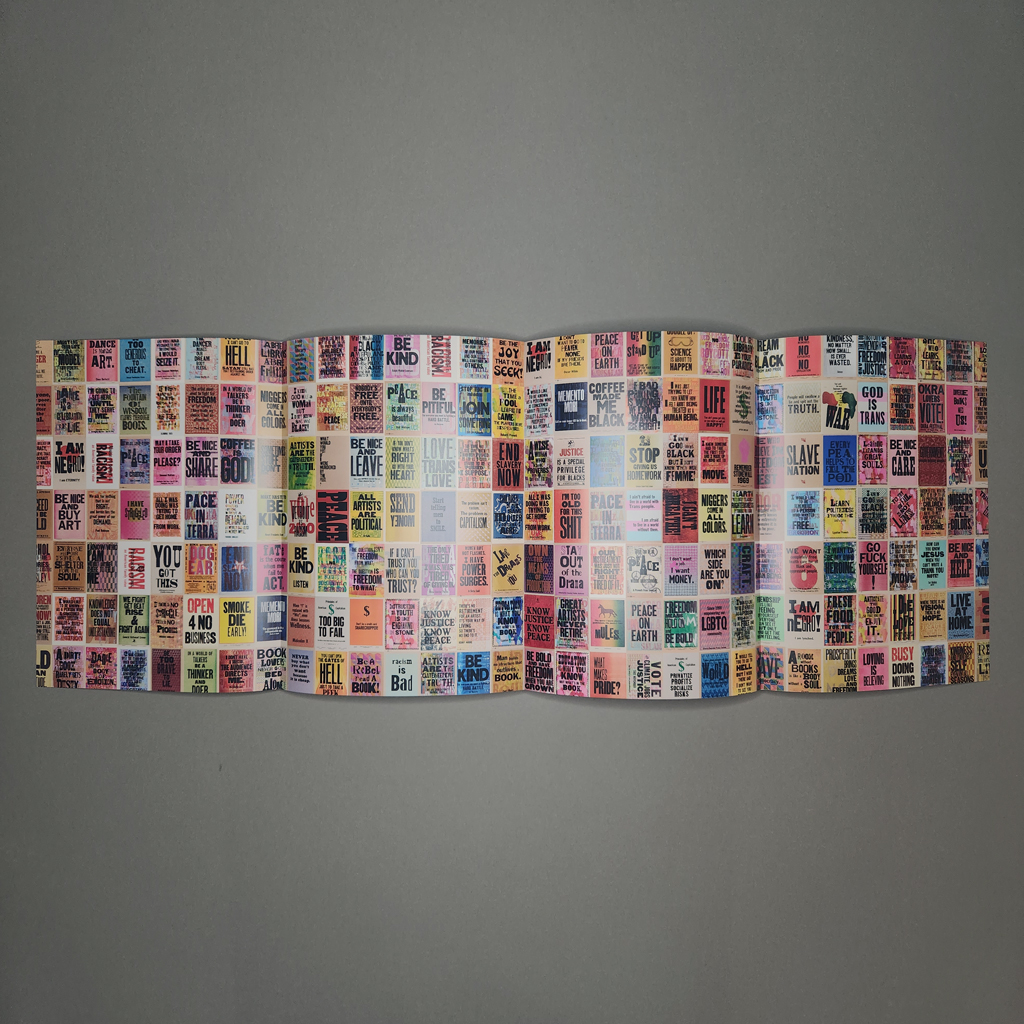

Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr.: Citizen Printer was published by the Letterform Archive in conjunction with an exhibition of the same title, curated by Kelly Walters. However, the new monograph is more than an exhibition catalog. While the exhibition boasts over 150 objects, the book amasses more than 800, all reproduced with impeccable quality. Two substantial essays, one by Walters and another by artist and scholar Myron M. Beasley, contextualize Kennedy’s work, including his own writings, which have also been included. Already the subject of a feature-length documentary, Kennedy hardly needs an introduction, but the short foreword by Austin Kleon establishes the basic facts: Kennedy is a man of letters (in more ways than one), an imperfectionist, a maverick who is nevertheless aware of the traditions he works in, and an artist (though Kennedy would dispute the term). Kennedy compares his work to spirituals and the blues. I would also add jazz. Kennedy is a virtuoso of quotation and improvisation, and without diminishing Kennedy’s idiosyncrasies and innovations, Citizen Printer shows the deep well he draws from.

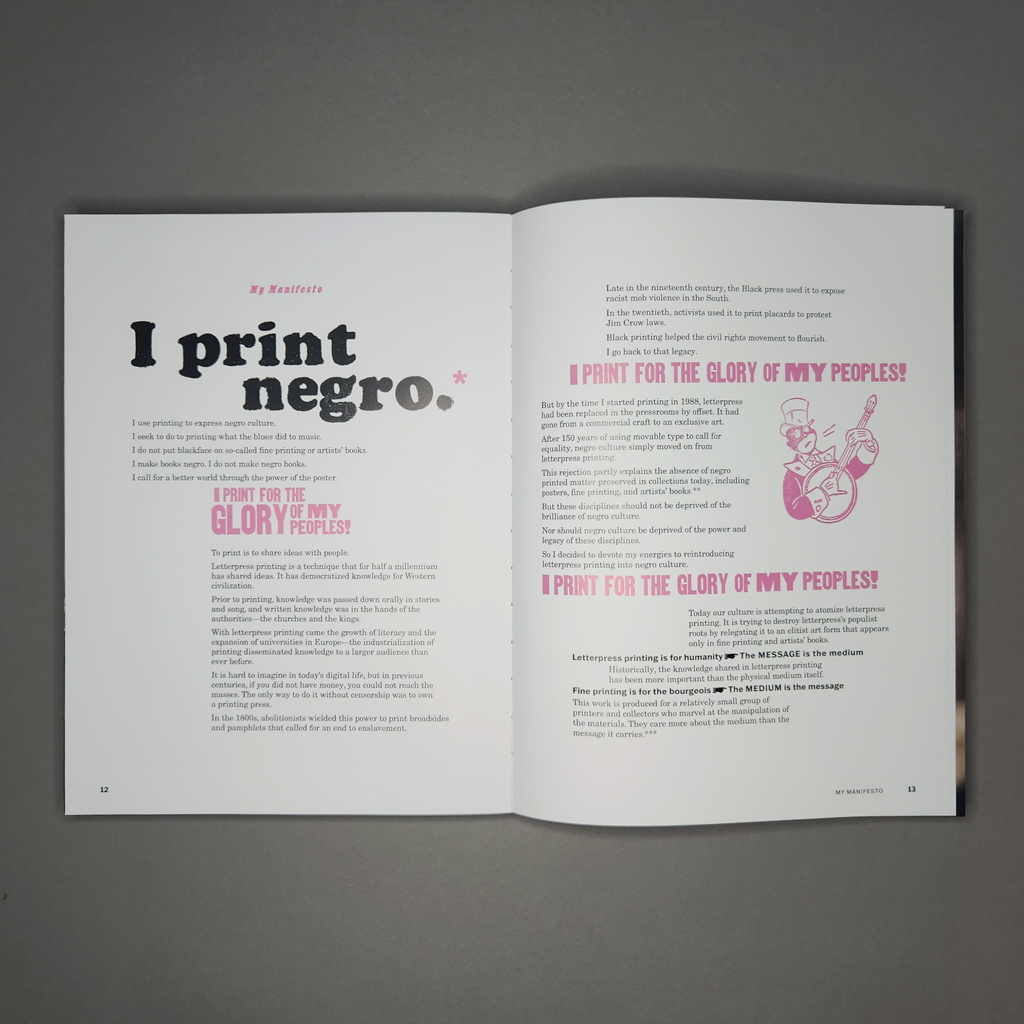

As an object, the book embodies the spirit and style of Kennedy’s posters. The raw boards and exposed spine (complete with a title printed on the folded signatures) seemed practically required for exhibition catalogs a few years ago, but they are a particularly thoughtful choice in this case. The boards evoke the chipboard Kennedy prefers printing on, and the overall unfinished feel captures his speed and “imperfectionism.” Inside, however, designers Gail Anderson and Joe Newton took few lessons from Kennedy’s “school of bad printing” — and this is a good thing. The book showcases Kennedy’s work without trying to replicate it. A pink spot color (picking up on Kennedy’s signature uniform) is used as an accent throughout, and Kennedy’s “My Manifesto” does include digitized wood type, but the essays and catalog are more restrained. This heightens the disruption caused by prints from Kennedy’s collection of racist cuts (minstrels, Sambos, and other caricatures) that haunt the book’s margins, indelible reminders that letterpress helped spread antiblack racism. When it comes time to present Kennedy’s work, no such devices detract from the reproductions, not even captions.

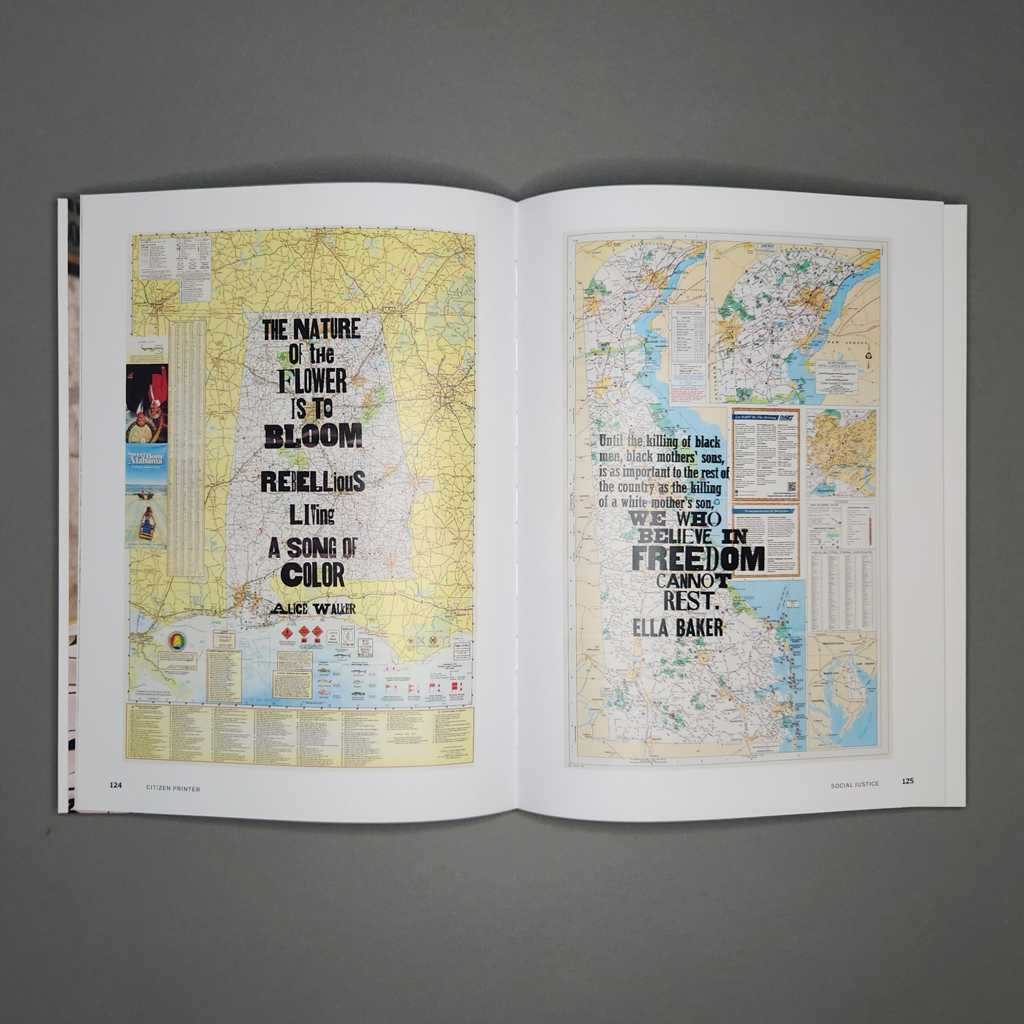

The quality of the photography and offset printing is truly exceptional. Many of Kennedy’s posters are given a full page, and those that are reproduced smaller still retain remarkable detail. This may be anathema among my fellow fans of letterpress, but hardly anything is lost in the translation from letterpress to offset. The printing also brings to life Aundre Larrow’s photographs, which are more often environmental portraits than an attempt to document Kennedy at work. These convey Kennedy’s humor and intensity if not the noise and chaos of his printshop, but Citizen Printer is not meant to recapitulate Proceed and Be Bold! in print. The book’s creators seem aware of what a monograph can do that a documentary cannot, and one of those things is to create a repository of Kennedy’s posters, which can be read for pleasure and inspiration, like the original prints, or referenced for research.

That said, Citizen Printer, while expansive, is not a catalogue raisonné. Kennedy’s works are not organized chronologically but rather into three broad categories: social justice, shared wisdom, and community. Their presentation, sans caption, certainly favors viewing pleasure over research. Nevertheless, the essays by Beasley and Walters are important scholarly contributions. In a field dominated by white scholars and practitioners, it is noteworthy that both contributors are Black academics with deep expertise in art and design in the African diaspora, and both are practitioners as well as scholars.

Beasley’s “Incorrigible Disturber of the Peace! Ink & Equity” is more biographical, rehearsing Kennedy’s departure from white-collar work to printing but also documenting lesser-known chapters. Beasley writes about Kennedy’s education and his “unschooling,” his MFA at University of Wisconsin—Madison but also his formative experience at Grambling State, a historically black university in Kennedy’s home state of Louisiana. The essay shows how certain projects respond to specific experiences — we can credit racist microaggressions at Indiana University, where Kennedy served as the first Black art professor, for his NappyGrams — while others come from a diffuse mix of personal and cultural influences.

Walters’ essay, “Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr., & the Legacy of Black Printing in America,” is less biographical and more contextual. She offers a succinct chronology of printed matter — from runaway slave notices and abolitionist newspapers to the Harlem renaissance, civil rights placards, Black Panther publications, and hip-hip fliers — and convincingly demonstrates that Kennedy has a nuanced understanding of this history. Kennedy’s command of Black print history is not just a matter of form and content but also social purpose. Identifying these precedents does nothing to diminish Kennedy’s originality. Rather, it brings into focus Kennedy’s ability to synthesize disparate sources into his signature style.

The breadth of Kennedy’s influences are also reflected in the catalogue. The impressive volume of his output is conveyed in a double gatefold with hundreds of posters arrayed in a grid. Even die-hard fans will discover prints they haven’t seen before. The quality printing means one can appreciate typographic details and dazzling layers of ink without the need for detail shots. This is essential since Kennedy is about spreading the word, not fetishizing the material traces of letterpress printing. Another way the book capture’s Kennedy’s ethos is by presenting multiple versions of the same poster. For Kennedy, it is important that each poster is a little bit different and a little bit off. The variety also helps explain how he has sustained his practice. In “Lessons from the School of Bad Printing,” his process sounds almost formulaic, but it is remarkably adaptable. Kennedy is serious, cynical, irreverent, hopeful — and always himself.

As an artist who works with proverbs and quotations, Kennedy himself has a knack for memorable phrases. If Citizen Printer indulges in some well-worn quotes, it also adds new voices and ideas to the considerable corpus of work on Kennedy. More importantly, letterpress and book arts, so attached to the materiality of print, can learn from Kennedy’s devotion to the spoken word. His voluminous and affordable prints aspire to the circulation and enduring impact of the quotes they carry. Yet, Kennedy doesn’t just repeat quotes; he engages with them critically. He subverts racist old aphorisms and turns them into affirmations. He elevates the wisdom of school children alongside the ancients and ancestors. Rather than merely celebrate it, Kennedy respects the power of the spoken and printed word. That means calling out those who abuse it as well as those who squander it. One hopes Citizen Printer will inspire others with printing presses to fully harness their power.

Leave a reply to Aundre Cancel reply