Last Pages

Rahel Zoller

2024

Edition Taube

Perfect-bound softcover

200 pages

6.25 × 9.25 in. closed

Offset printing

Review by Michael Hampton

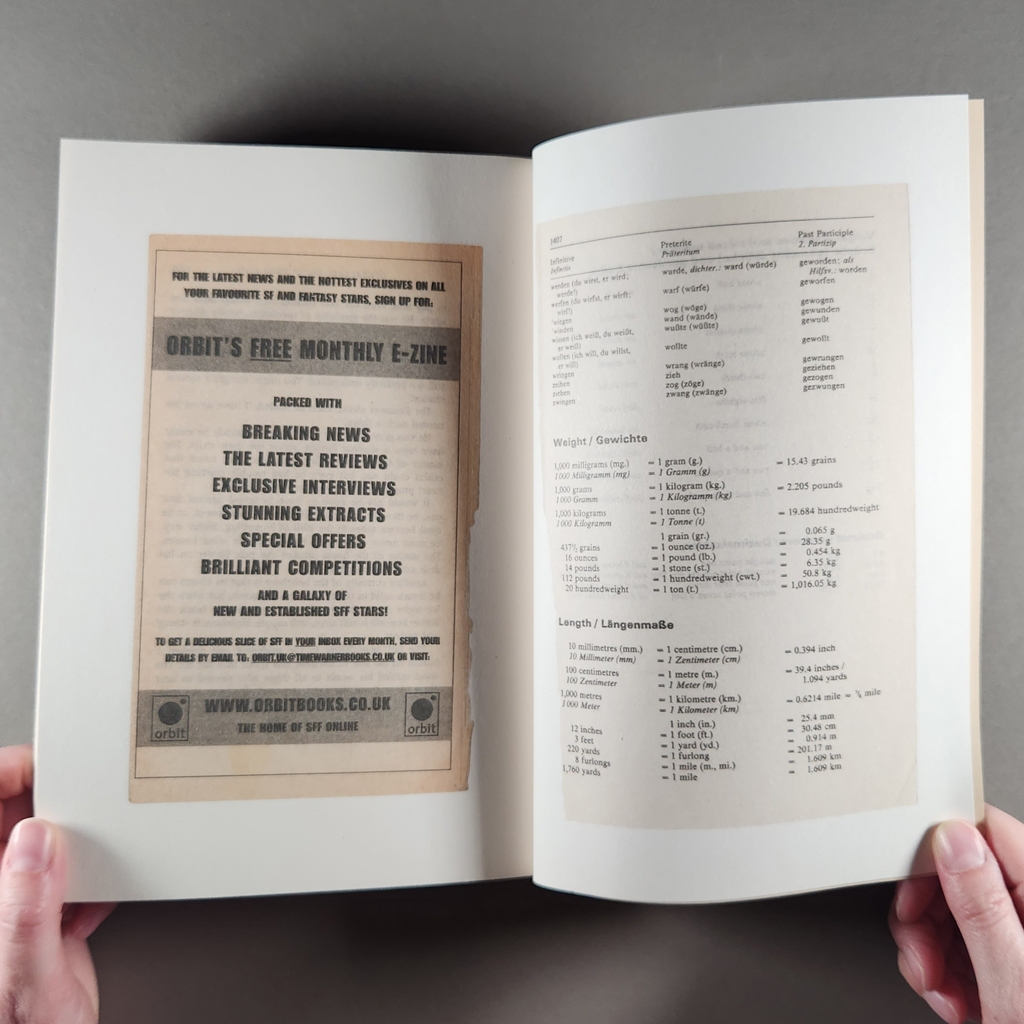

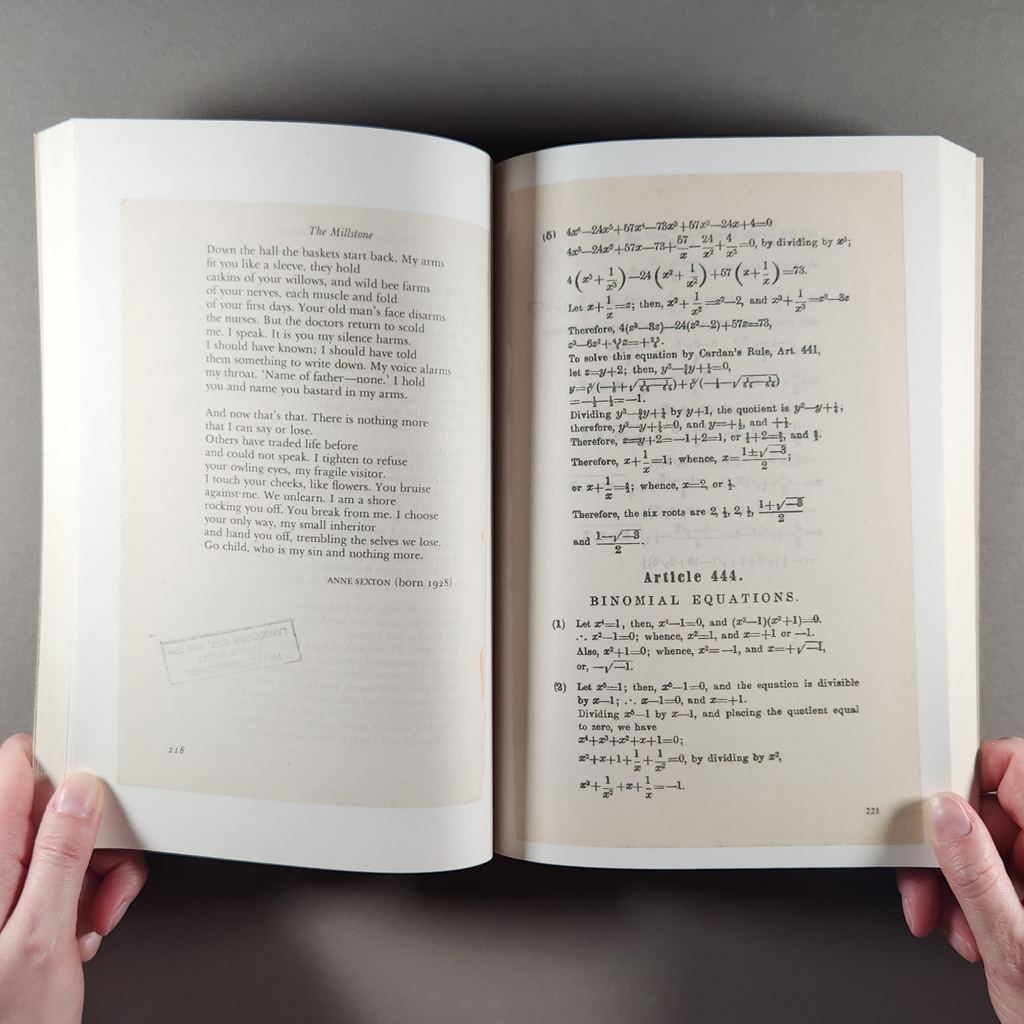

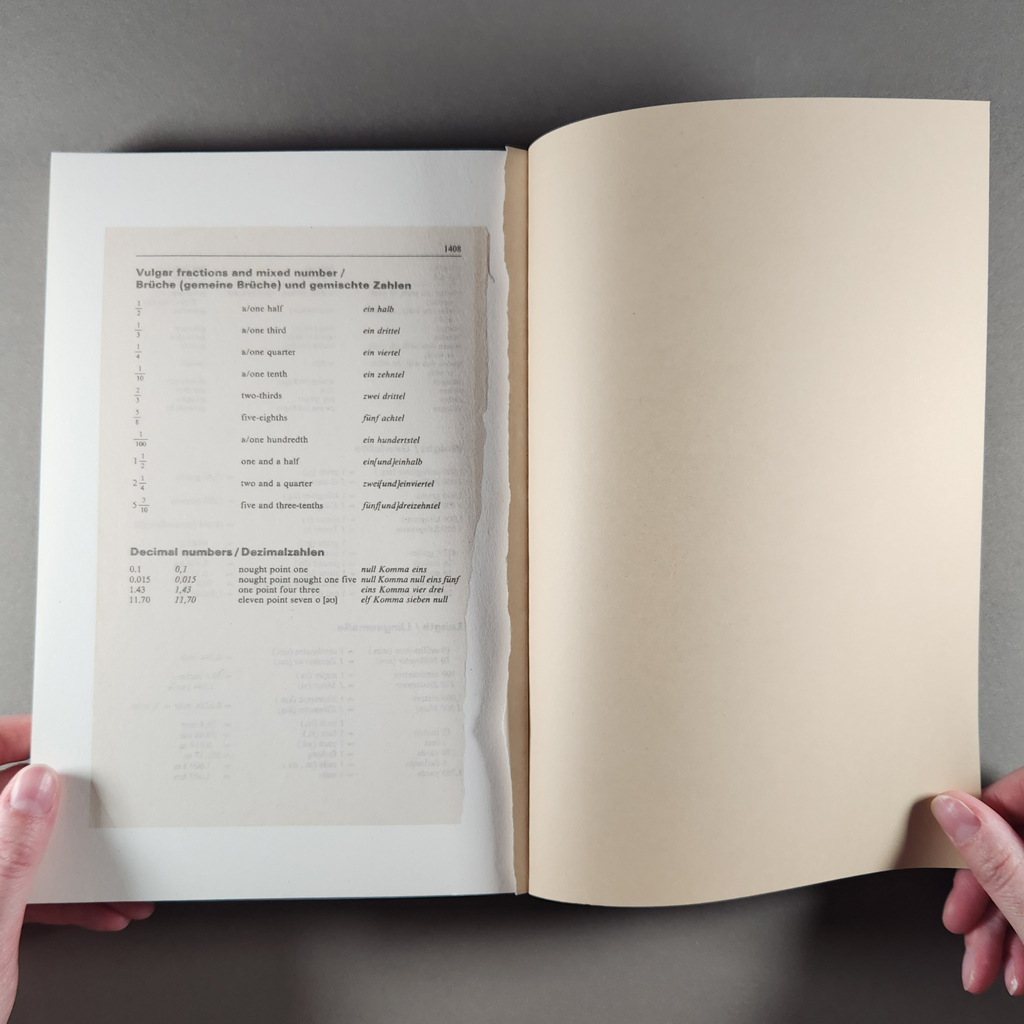

In her extended collection of illustrated final page samples, torn from discarded books found in various street book swaps, recycling bins and gutters of European cities during the summer of 2022, Rahel Zoller presents the reader with an extended cache of high and low material that demonstrates her bibliographic athleticism and dedication. First, she had to spot and salvage this detritus, then organize it into Last Pages, which displays a bank of serendipitous samples in Dutch, English, French, German Fraktur, Norwegian, and Vietnamese.

Following in the footsteps of that great 17th century antiquarian scavenger, John Bagford, whose life spent going through the binder’s waste of London’s printshops resulted in his two massive folios of scraps, Fragmenta manuscripta and Fragmenta varia, Zoller’s book is a highly personalized collection.[1] Lacking any standard paratextual apparatus (Table of Contents, Introduction, Colophon), the 200-page picture gallery is no Dewey Decimal-systemized library, parceled up into categories and genres.

No, everything is put together here in a dissonant, jumbled pile, “a textual menagerie of chance” as the blurb on the bespoke Edition Taube bookmark puts it, confirming Liam Gillick’s observation in Industry & Intelligence (2016), that contemporary art is “a pile” and “essentially an accumulation of collapsed ideas.” So, Zoller is on interdisciplinary message here. There is however a discernible ordering principle: sequential page numbers of vagrant loose leaves (reproduced as color facsimiles) which start at number 15 and continue to 1408, the very first page being an inapplicable Author Index located at the very beginning rather than end of this bizarre book!

Diving in, it soon becomes clear that Indexes, General Bibliography pages and Acknowledgements abound, quite naturally (even a Pronunciation page), but as the former are divorced from any referential contents, their striking beauty as stranded typographic artefacts is disclosed. We get self-help lit aplenty, topics such as binomial equations and karate, a hymn sheet, a recipe for a fragrant tea blend, followed by its author, Patricia Lousada’s, bio (each last page has been photographed back and front, appearing as recto and overleaf verso throughout) and learn that A Man for All Seasons had an alternative ending, plus, via a helpful running header, that noir detective Mike Shayne was on the case in Murder Wears a Mummer’s Mask.

So, narratives start, go nowhere, and end abruptly, each acting as an inadequate terminal précis of what has gone before, stories or discourse we can guess at but not immediately consume. Typically tantalizing as a random concluding sentence is

Bang went the cracker and out fell the usual assortment of a paper hat, a bad joke, and a lucky charm.

The sole identifiable text (speaking personally and without any Googling), is Stephen Knight’s The Final Solution, an outlandish, and now discredited Jack the Ripper hypothesis involving the British royal family. So, detection or reverse engineering of missing titles, is one of the interactive reader games which Last Pages sets up — a pastime which could very easily become obsessional. In contrast, the special offer and order pages of defunct imprints such as Grafton Books and design elements like the ironically named Futura typeface hang redundantly on white backgrounds.

Faded material piles up: yellowed and autumnally toned in subtle ways, embrittled acidic pages, and the cryptic loose leaves of books doubling as the actual evidence for “special types of chronographs” in Craig Dworkin’s memorable phrase.[2] An inviting blank page is graffitied with a child’s red crayon scrawl, a classic oval stamp in violet ink, courtesy of Poplar Public Libraries, London. In some respects, these lost, last pages resemble palms that must be read for their fate lines and forks, possibly even used stochastically for bibliomantic purposes.

So much for page view analytics then, Rahel Zoller’s Last Pages is curated to deliver a series of hits, the ultimate being that its own final page has itself been torn out, in a moment of whimsical, designer vandalism, leaving us to wonder about its content and fate, or even, perish the thought, tear out and scatter its own facsimile pages to the four winds! Rather that, than see odd disbound vellum pages from Latin incunables used to make lampshades, a fad in 1930s stockbroker belt England!

Inevitably, anything marketed as last will be elegiac in tone, suggestive of an imminent global doomsday. Take this editorial description of Stanley Schtinter’s Last Movies and compare it with Last Pages, the sentiment here virtually identical:

Last Movies antagonises the possibility of survival in an age of extremity and extinction, only to underline the degree of accident involved in a culture’s relationship with posterity.

So, in an age of increasing geopolitical disturbance and uncertain horizons, Zoller’s trail mix of synecdochic samples — or ‘speciments’ in Bagford’s early modern jargon — the lost limbs of phantom bodies, comprise a sort of reliquary, perhaps with eschatological undertones, for the armchair scavenger with a taste for bibliographic mysteries.

[1] For more on Bagford, see my review of Whitney Trettien’s book, Cut/Copy/Paste:

Michael Hampton, “Cut/Copy/Paste: Fragments from the History of Bookwork,” Openings: Studies in Book Art Vol. 6, No. 1 (2023) BR 1–2, https://journals.sfu.ca/cbaa/index.php/jcbaa/article/view/99/185.

[2] Craig Dworkin in Michael Hampton, Against Decorum (Information as Material, 2022), 1.

Leave a reply to Artists’ Book Reviews Cancel reply