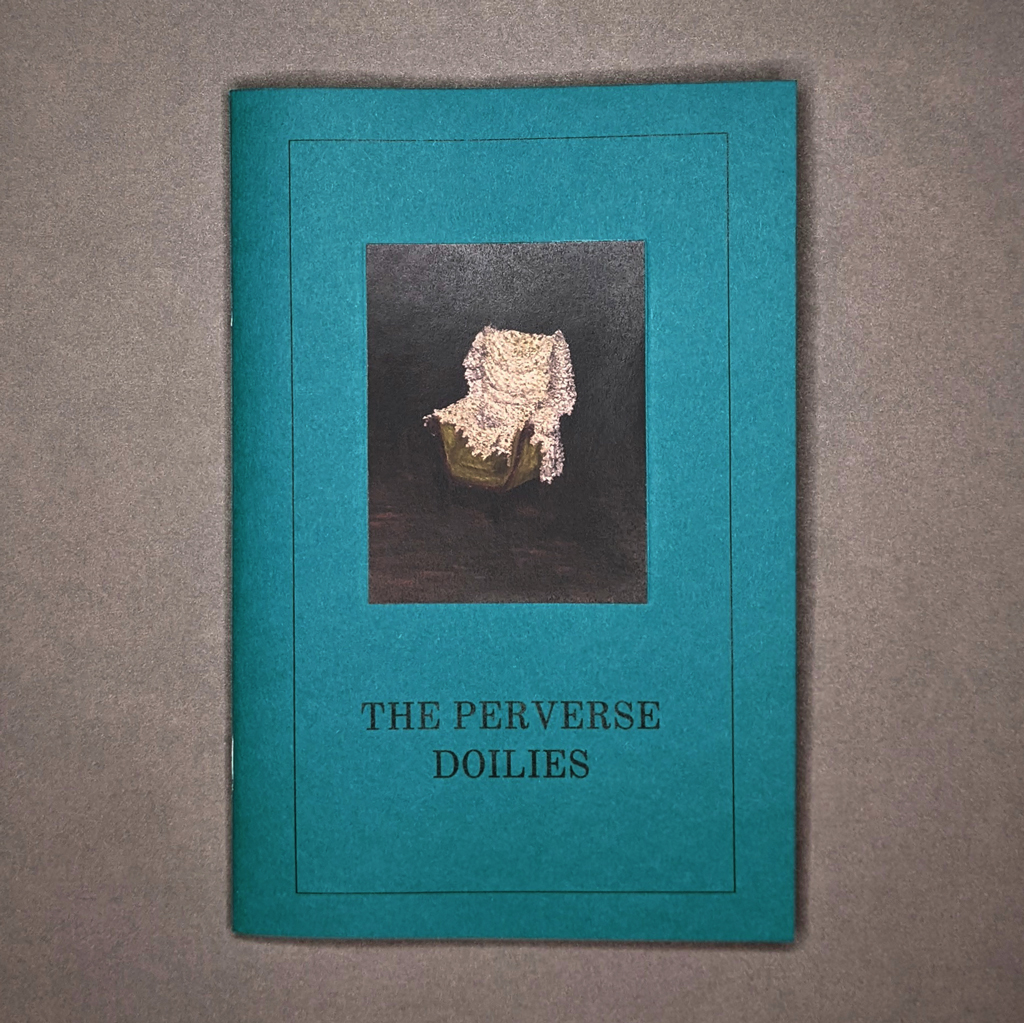

Neil Majeski

The Perverse Doilies

From the series: The Last State or the Penultimate

2019

4.5 × 7 in. closed

20 pages

Saddle-stitched, softcover pamphlet

Inkjet and laser

[In a departure from the usual Artists’ Book Reviews format, this mini review is part of a series on Neil Majeski’s pamphlet series, The Last State or the Penultimate. The first of these mini reviews covered Majeski’s series as a whole.]

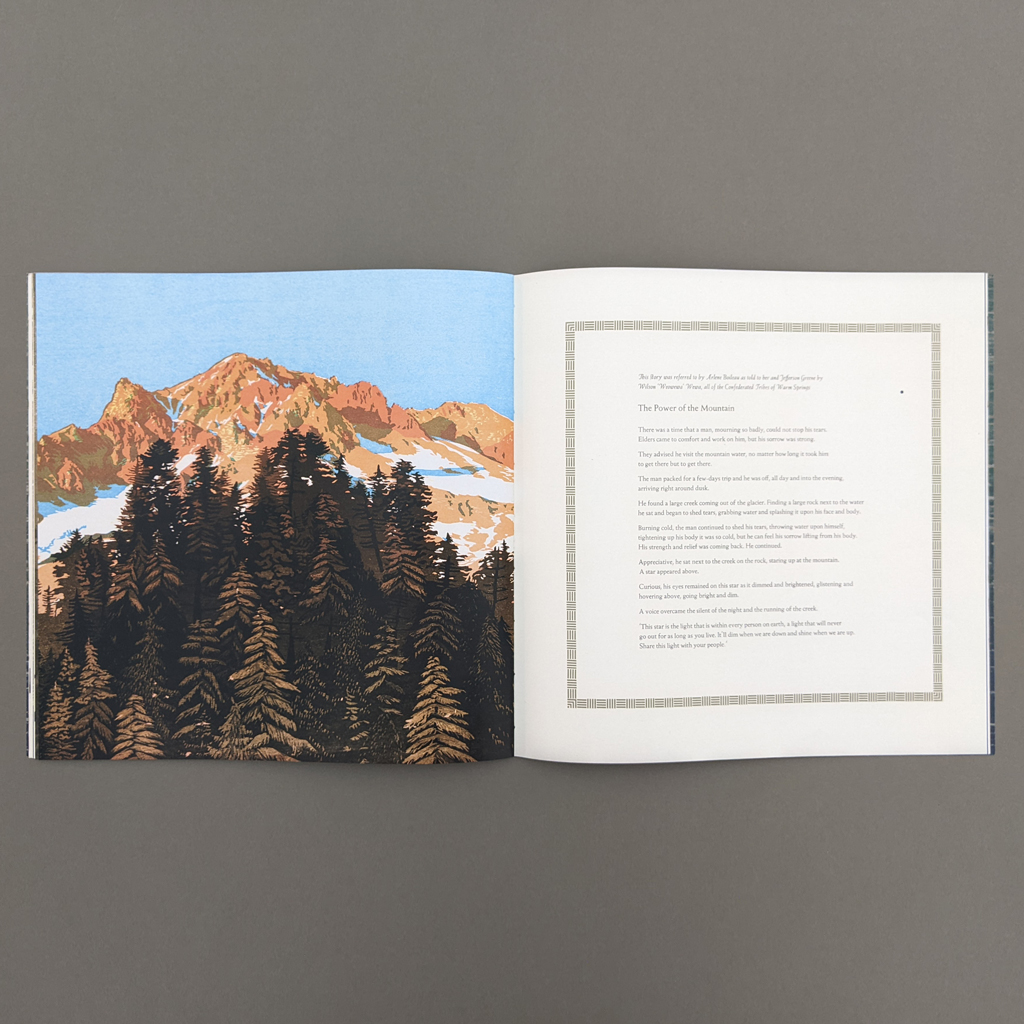

The Perverse Doilies begins, like much of Majeski’s work, in an antique shop. However, the pamphlet begins not with the eponymous doilies but with a mystery object. Leaving that mystery unsolved, Majeski tops the object with a gyroscope and dubs his readymade the “Telecommunic Spacecutter” before continuing on with a reflection on André Breton’s encounter, in Nadja, with a similarly elusive object at a flea market. Majeski includes photographs of both his and Breton’s mystery cylinders. Presumably the reader could identify Majeski’s object, and maybe Breton’s, but that is beside the point. Majeski wants to know what Breton means when he calls his object “perverse — at least in the sense I give to the word and which I prefer.” This sense of perversity is present throughout the Last State or the Penultimate series, though its connotations always shown, never told. It manifests in Majeski’s subtle manipulation of the tensions between narrative and non-narrative, between text and image, and among media, from photography and painting to the book itself.

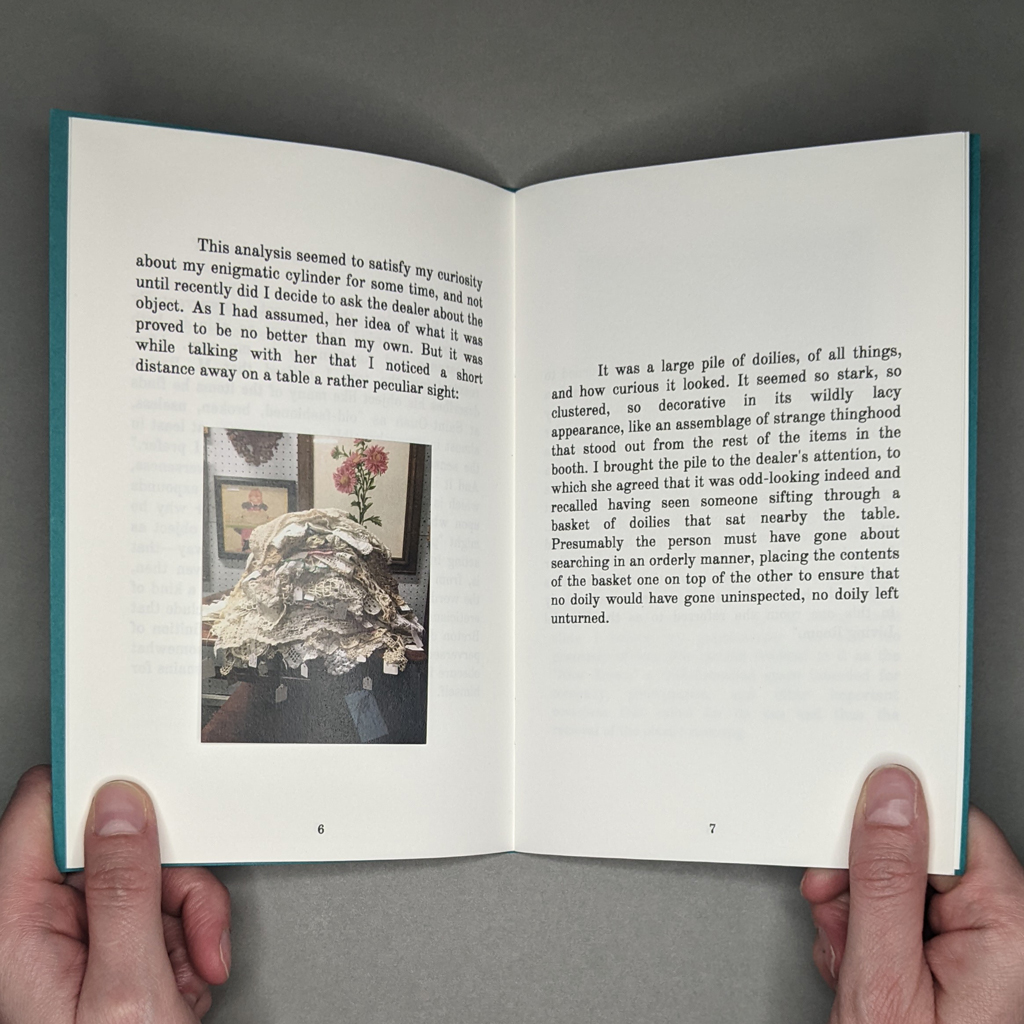

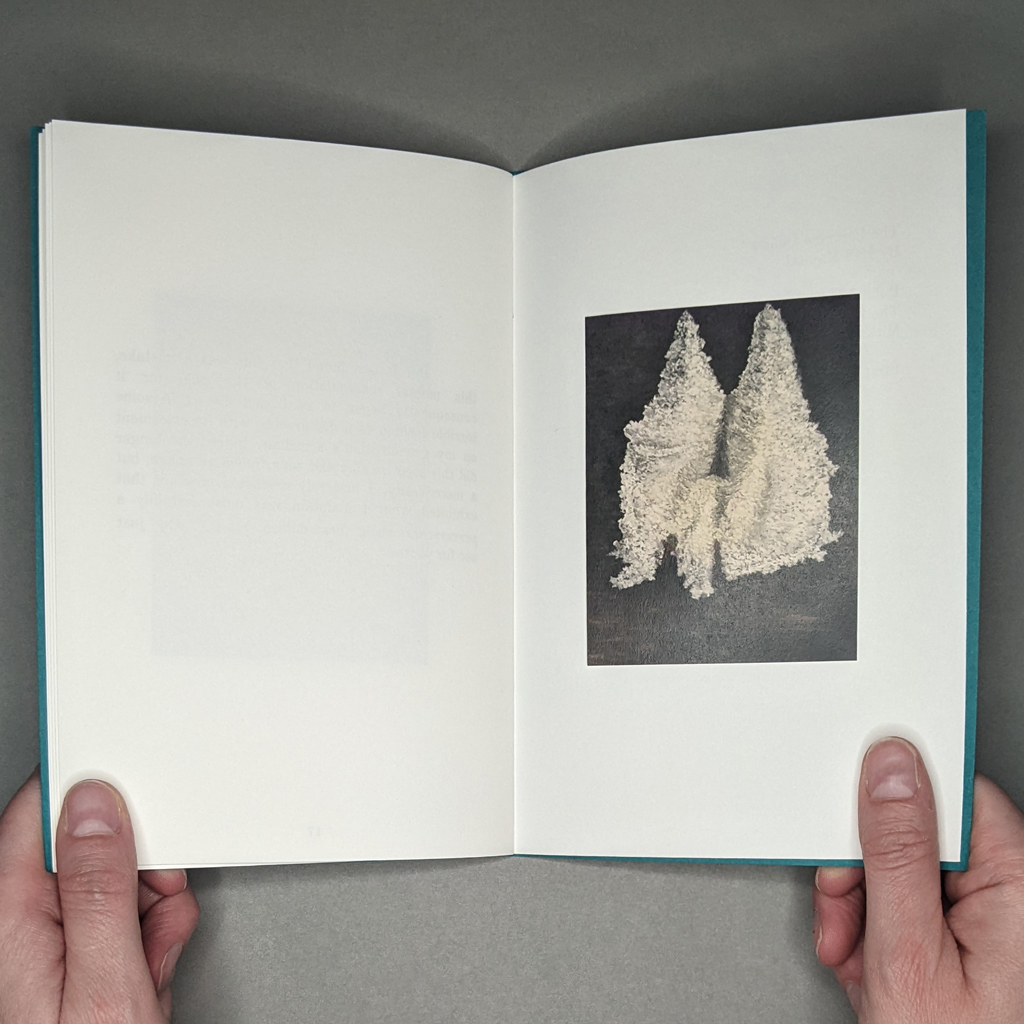

What is perverse is not merely outside norms or expectations, it is willfully so. A perverse object, then, has some sort of agency. Enter the doilies. Majeski finds the doilies, piled in an “assemblage of strange thinghood” in the same shop, just after his mystery object. Struck, he confers with the antique dealer, who believes a customer must have emptied the doilies from a basket and piled them one by one. This hardly dispels the sense of agency. If anything, the urge to examine dozens of doilies illustrates the power they exert. Even in the accompanying photograph, the doilies have an impressive visual presence. They slump into a monumental mass of macrame and lace from which numerous price tags dangle, suggesting the individual objects that comprise the assembly.

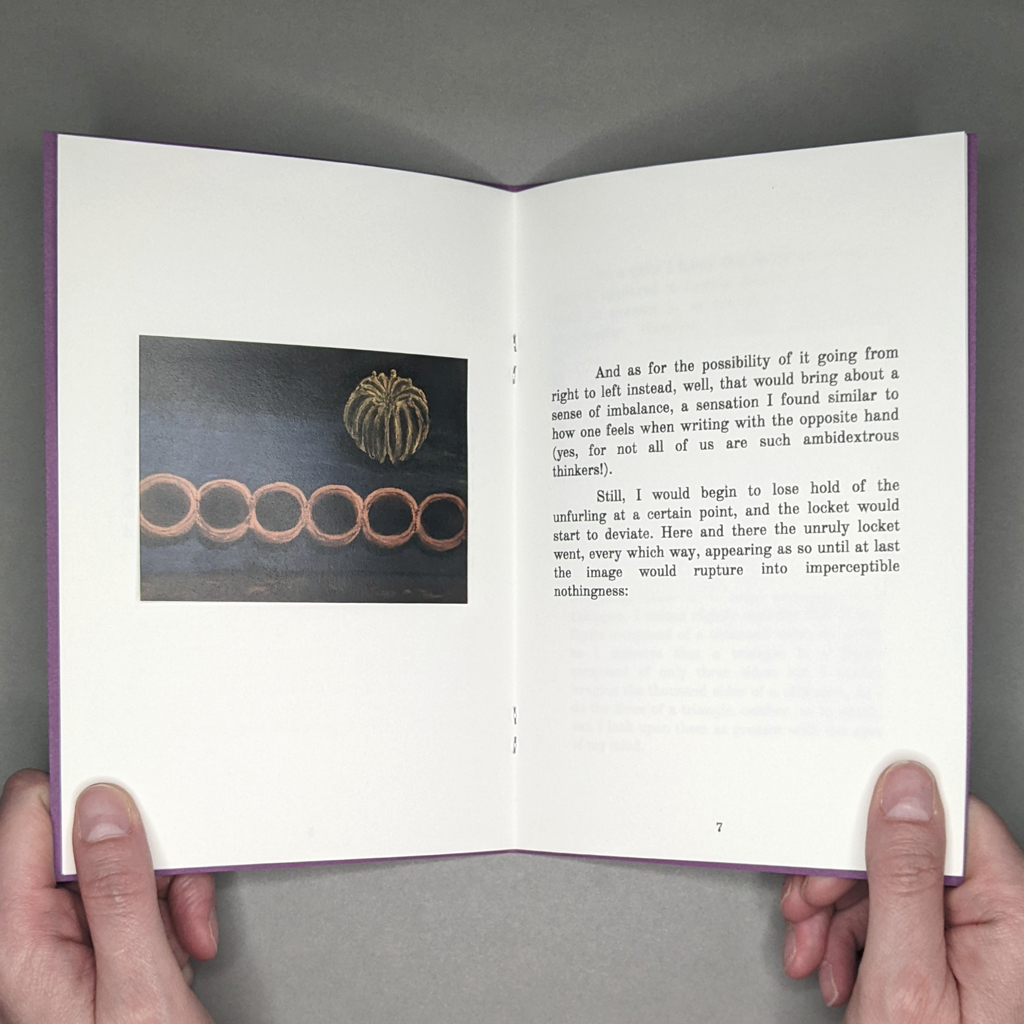

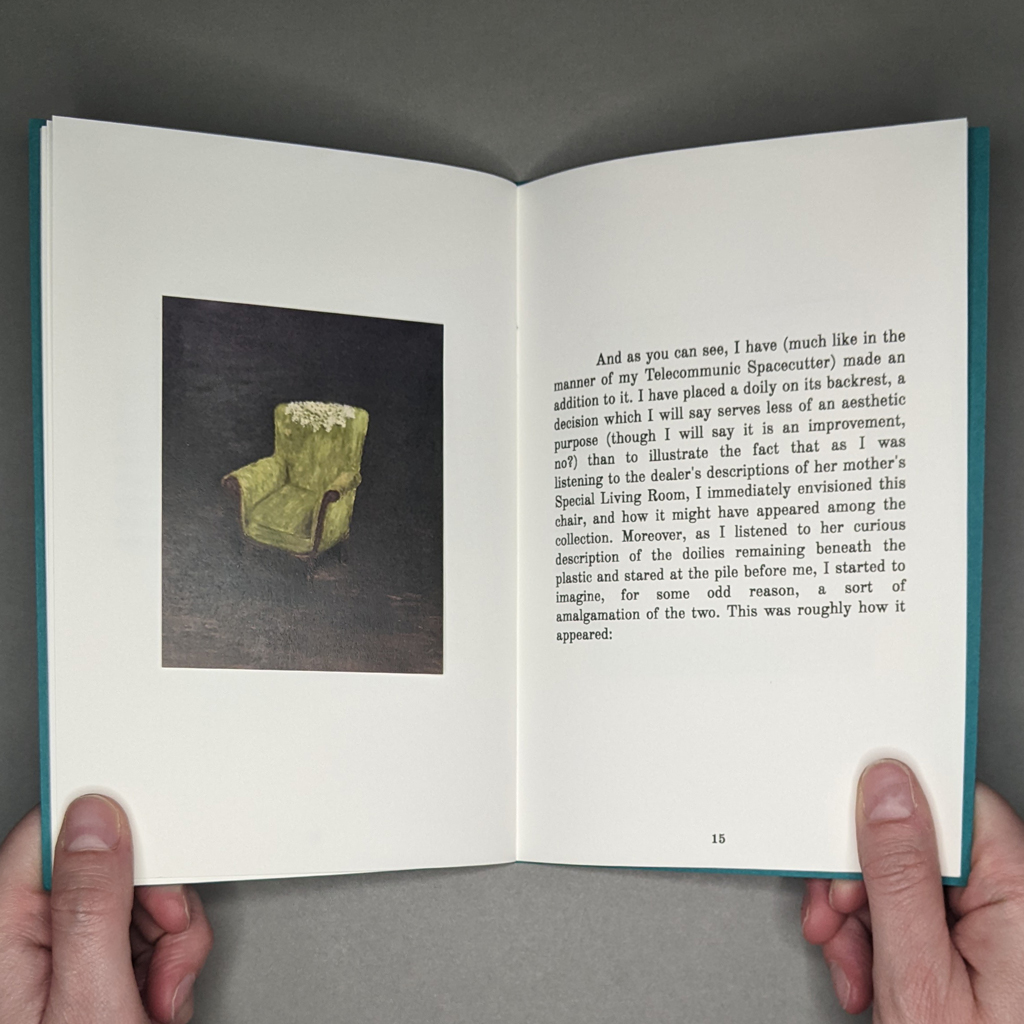

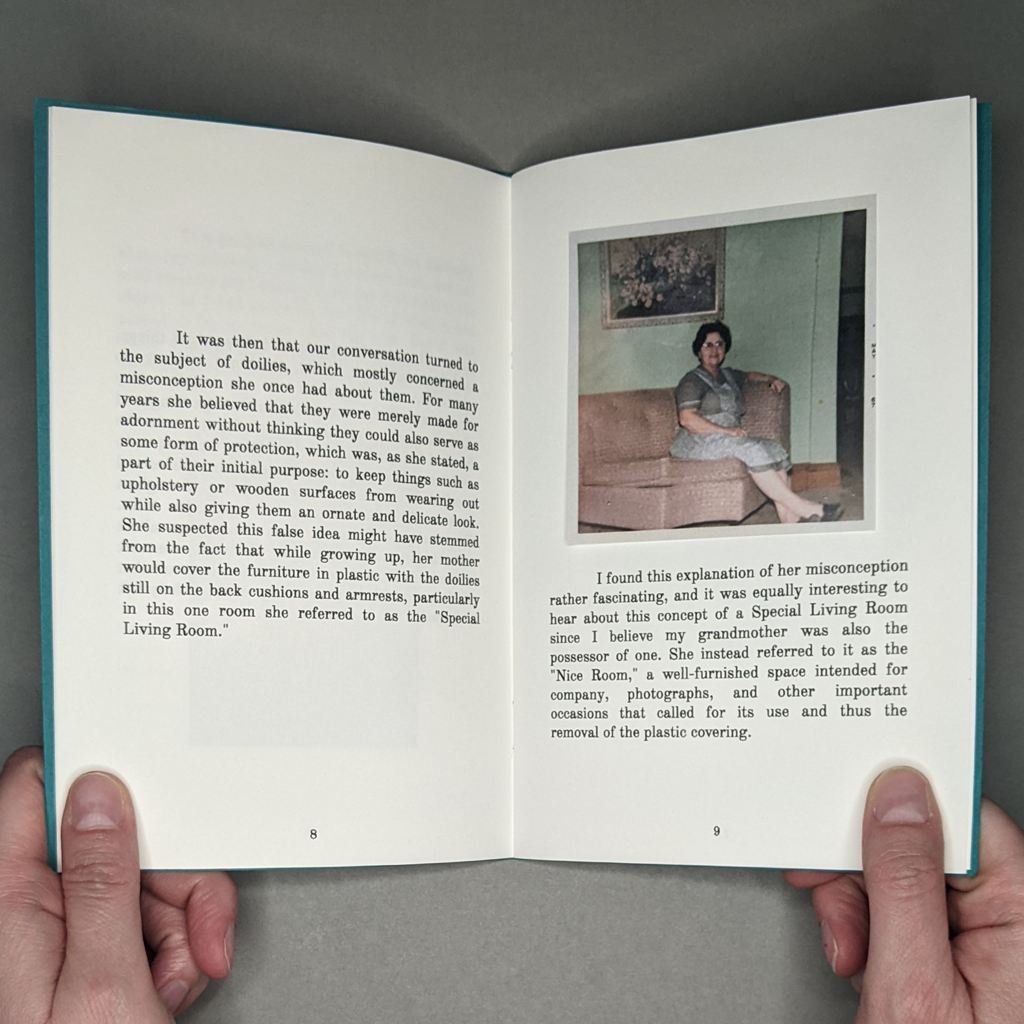

From doilies, which are designed in part to protect surfaces, the conversation turns to the plastic-wrapped living rooms of the antique dealer’s mother and Majeski’s grandmother, respectively. Hearing the antique dealer describe redundant doilies under the protective plastic in her mother’s “Special Living Room,” Majeski mentally transplants these into his grandmother’s “Nice Room.” Mentally and materially, since he illustrates the transformation in paint: a green armchair without and then, with the turn of the page, sporting a doily. By enlisting the reader to transform the armchair, the book’s interactivity enhances the move from mental to material.

The transformation also cleverly collapses temporalities, as Majeski does throughout the pamphlet series. He shares two photographs of his grandmother’s Nice Room, but both are from before his time (the room was decommissioned before he ever visited). The chair outlasted the Nice Room, and now survives in Majeski’s memory. As a mental artifact, he can manipulate it instantly: “And as you can see, I have…made an addition to it. I have placed a doily on its backrest….” But this instantaneous transformation is a feature of the codex, the turn of the page. In fact, Majeski’s mental exercises are in tension with his chosen medium of paint, with its evident materiality and presumed slowness. The book form makes a coherent narrative out of the disparate durations of photographs and paintings, memories and imaginings.

It is hard to say whether Majeski’s imagination or the objects themselves are the catalyst of that narrative. He mentally merges the armchair’s doily with a plastic cover, creating “a monster, a bizarrely crocheted creature,” which he renders for the reader in paint. With the turn of the page, the chair is completely engulfed. The perverse doily creeps beyond the outline of the chair, an amorphous mass with a gaping maw (though perhaps this last detail is the work of my own imagination). The text ends here; the painting is punctuated by an empty verso across the gutter.

If the book continued, no doubt a tangle of macrame would escape the borders of the next composition. I am reminded of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice in Fantasia, where an army bewitched brooms runs amuck, endlessly replicating and mindlessly repeating the task Micky Mouse has set for them. Or Strega Nona, where Big Anthony nearly buries his village in an avalanche of pasta. Majeski’s fairy tale ends before the master returns to restore order — or perhaps the doilies are in charge. The perverse doilies certainly exhibit a willful disregard for expectations, but there is an equally powerful, albeit less fantastical, lesson about the agency of objects. Majeski writes that his grandmother’s Nice Room “fell into disuse, becoming less of a living room than a kind of lifeless space full of fancy, preserved furniture.” This is the phenomenon at the center of The Perverse Doilies. The mid-century vogue for protective plastic and formal dining rooms may have passed, but it is not hard to see how — to invoke one more pop culture reference, this time Fight Club — “the things you own end up owning you.”