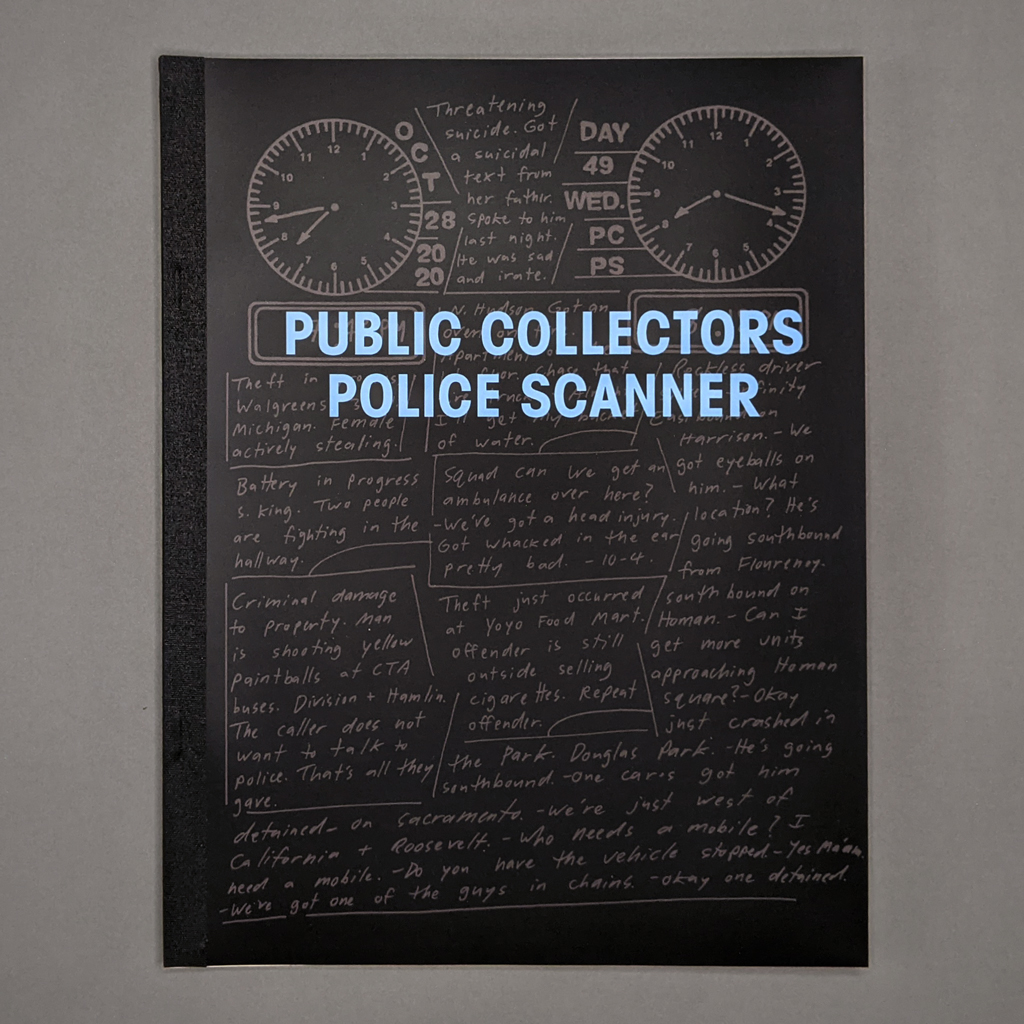

Public Collectors Police Scanner

Marc Fischer

Public Collectors

2021

8.5 × 11 in. closed

90 pages

Side stitch and fabric tape binding

Risograph and digital printing

Proponents of the “thin blue line” assert that the police are the only thing preventing society from descending into violent chaos. A coyote in an alley, a bank robbery, missing children, and reckless driving: chaos abounds in Public Collectors Police Scanner. Chicago artist Marc Fischer comes to a different conclusion, however, about root causes and possible solutions. Fischer’s initiative, Public Collectors, is dedicated to making important but obscure(d) cultural artifacts public. To that end, Fischer listened to and transcribed the police scanner in Chicago for seventy-five days straight and compiled his hand-written notes into this often-overwhelming book.

The bulk of Police Scanner is scanned and Risograph printed directly from Fischer’s original, letter-sized notes. The format served as a creative constraint for each listening session: one page per day for an average of about forty-five minutes. Fischer details his methodology in the book’s introduction, including ethical decisions around excluding race, last names, VIN numbers and other identifying information. The end sheets, photographs of Fischer’s desk, document the chaos of the process itself. The side-stapled, taped binding further lends an air of low-fi urgency. Fischer’s handwriting powerfully attests to the challenge, speeding up and struggling to organize fragments of narrative as they are relayed among callers, dispatchers, and officers.

Events unfold relentlessly with no regard for conventional storytelling, nearly numbing the reader with uniform intensity, whether funny or tragic. Nevertheless, certain moments do break through the noise. Some are chilling: “Female keeps whispering the address and hanging up.” Others are absurd. A personal favorite of mine: “When you finish with lunch can you head over to the Department of Finance on Pulaski? They’ve got a dispute with an employee over money.” Fischer himself mines the potential for poignant humor in a related publication, Chest Wound to the Chest, which arranges excerpts from Police Scanner into a single long poem. (As a separate pamphlet, this poetic intervention allows Fischer to explore the fascinating rhetorical aspects of the project without departing from his documentary approach in Police Scanner.)

Since the book’s content reflects the vagaries of reality, the only narrative development is the book’s own layout, which conveys Fischer’s growing facility at following and organizing events as they occur. Police Scanner straddles documentation and performance, a choreography of disconnected chance operations that accumulate to reveal structural societal problems. Fischer tries columns, rows, even numbering events as they unfold wherever there is room on the page. On September 15, text funneled into a narrow column chronicles a suicidal man on a ledge. The empty white margins perhaps also indicate the emotional toll those seventeen minutes took on Fischer. On November 2, he writes: “I refuse to listen to the police scanner on my birthday.”

Birthdays aside, Fischer reflects in his introduction that the situation on the streets changes very little from day to day, even with major events like the 2020 election. Ongoing catastrophes, however, like the opioid crisis and Covid-19 pandemic loom in the background of many pages. Teachers witness child abuse during online classes or call for wellness checks on missing students. Fischer reminds the reader that then-mayor Rahm Emanuel closed half of Chicago’s mental health clinics in 2012, the impact of which cannot be overstated.

From the relentless repetition, the reader gets the impression that these systemic problems actually reflect the system working as intended. On November 6, police are sent to Home Depot to “see Brian about the day laborers and ask them to move off the property.” The same day, police are told to disregard a call because “it’s just the usual alley drinkers.” Systems like health care and labor markets are ultimately managed by the police. Since calls often come from businesses, this whole process plays out on a strange verbal map of brand names and private property. The resulting juxtapositions are often striking: “Bucket boys in front of Tiffany’s on Michigan.” One realizes just how little public space there is, usually an alley or a street. The gulf between the city’s aspirational street names and the events that play out on them is equally wide: domestic violence on King, a robbery at Jefferson and Madison.

Policing itself is, of course, one of the pervasive systems behind each individual event. Its rhetoric reveals its values and assumptions, and ultimately the inadequacy of policing to solve the problems it confronts. “Resources” refer to attack dogs, not to social programs. Victims are characterized as insensitively as perpetrators. Racialized and gendered descriptions are so habitual that a dispatcher alerts police to a “female pit bull” as if that would help identify the dog or explain its behavior. Amid the jargon and acronyms, a dispatcher might throw in a “bon appetit” or “okey dokey artichokee,” reminding the reader of the human subjectivity – for better or worse – behind each voice on the scanner.

In these unguarded moments lies the value of a project like Public Collectors Police Scanner. Fischer bears witness to the system of policing that is ostensibly for, and funded by, ordinary citizens like himself. Everyone shares this responsibility. Fischer is also quick to say that the police scanner doesn’t tell the whole story. After all, not every crisis leads (or should lead) to a 911 call, as police reformers and abolitionists are quick to point out. But it does paint a more complete picture of policing than most citizens receive from news and entertainment media. Fischer encourages his readers to listen to their local police scanner for themselves, and the insights gleaned from Police Scanner demonstrate the value of doing so.

Leave a comment