Neil Majeski

Music of the Uncanny Soundscapes

From the series: The Last State or the Penultimate

2020

4.5 × 7 in. closed

20 pages

Saddle-stitched, softcover pamphlet

Inkjet and laser

[In a departure from the usual Artists’ Book Reviews format, this mini review is part of a series on Neil Majeski’s pamphlet series, The Last State or the Penultimate. The first of these mini reviews covered Majeski’s series as a whole.]

Neil Majeski’s Music of the Uncanny Soundscapes is the last pamphlet I will review from his series, The Last State or the Penultimate. The book fits thematically and stylistically with the others, but its subject matter marks a departure. Whereas the rest of the series centers on images and objects, Music of the Uncanny Soundscapes is about sound and music. It is also, however, about thought and perception. It is about hearing things and seeing things (in both senses): perceiving what is there and imagining what might be.

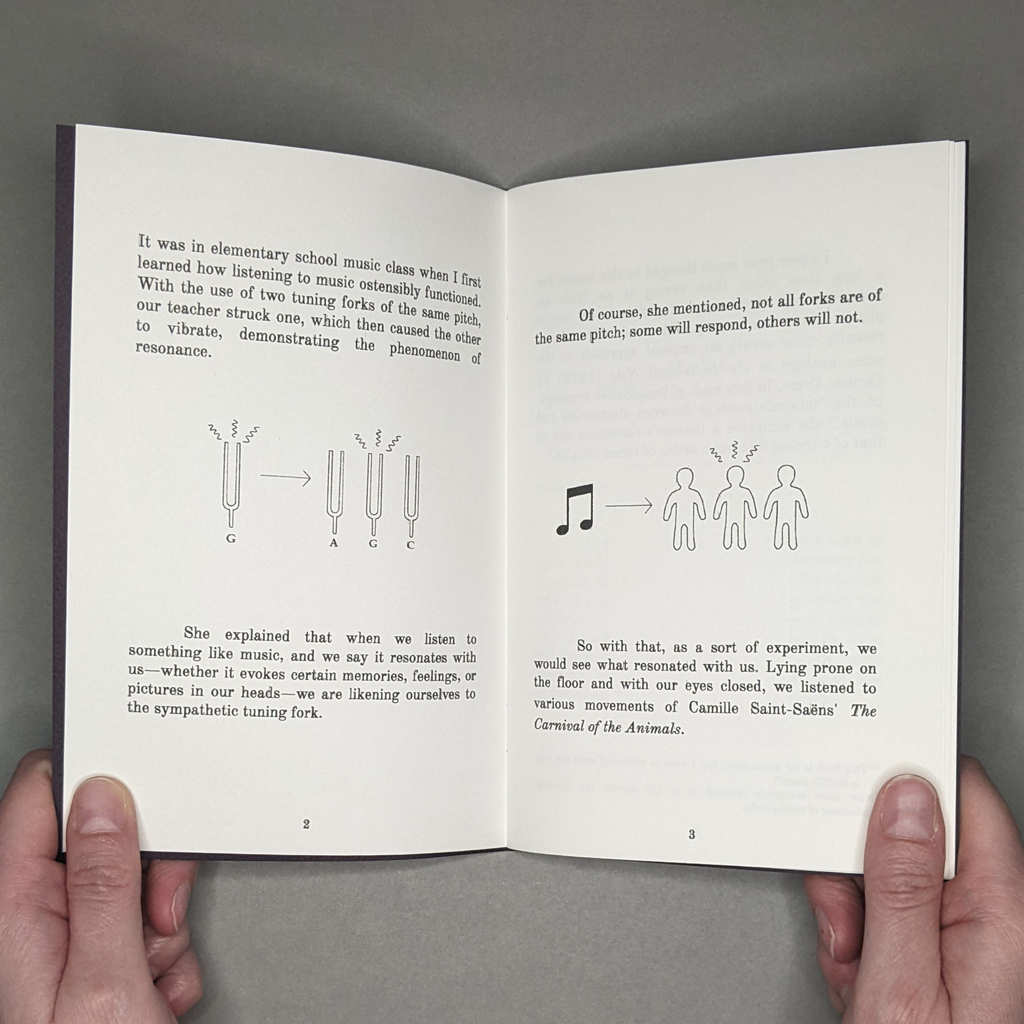

The short pamphlet has four distinct sections, though only the postscript is labeled as such. The first three are different approaches to the theme of resonant frequency. First, Majeski reminisces about an elementary school music lesson wherein tuning forks illustrate resonance scientifically but also metaphorically, as in music resonating with an attuned listener. Next, Majeski comes across a copy of the 1972 book An Individual Note, in which the groundbreaking composer Daphne Oram instead metaphorizes the music listener as a tuned circuit. Illustrated with textbook-style, duotone diagrams, Majeski explains the technical aspects of tuned circuits as well as Oram’s more philosophical musings.

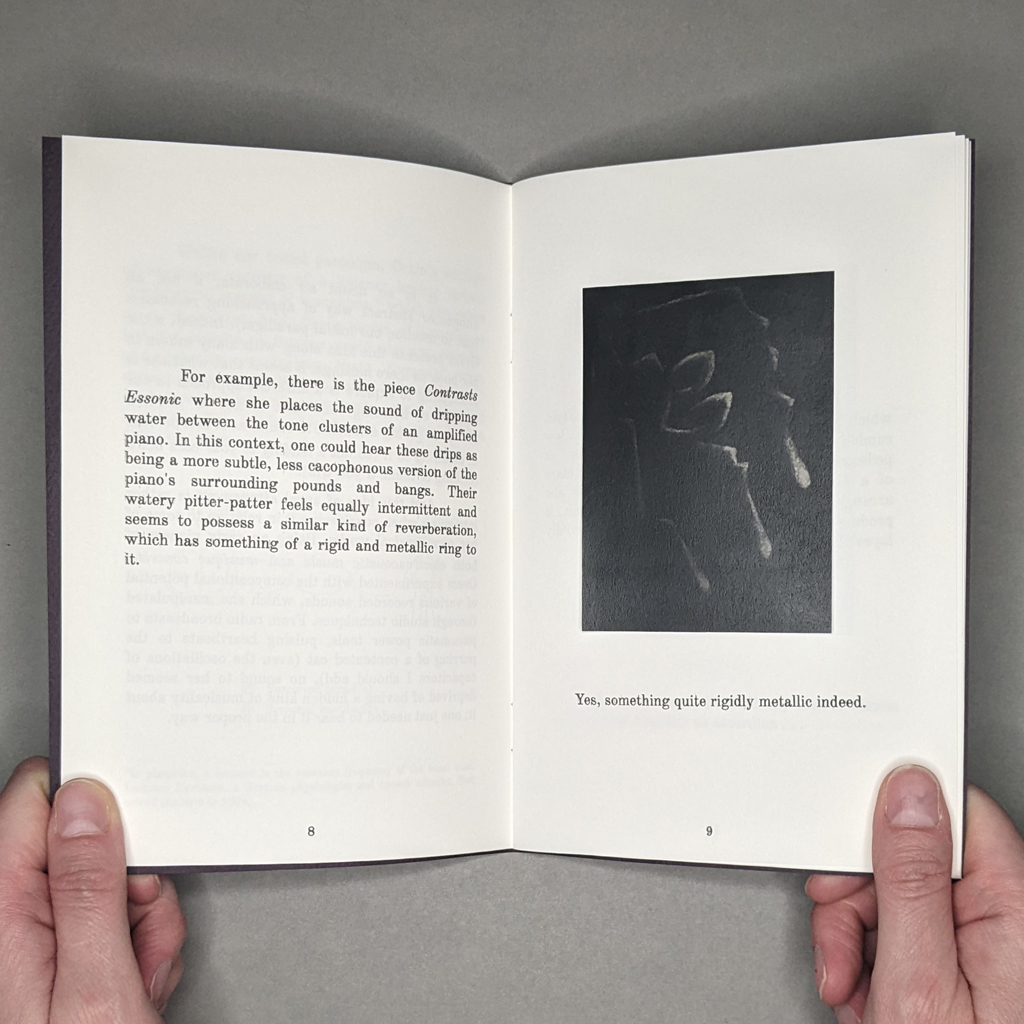

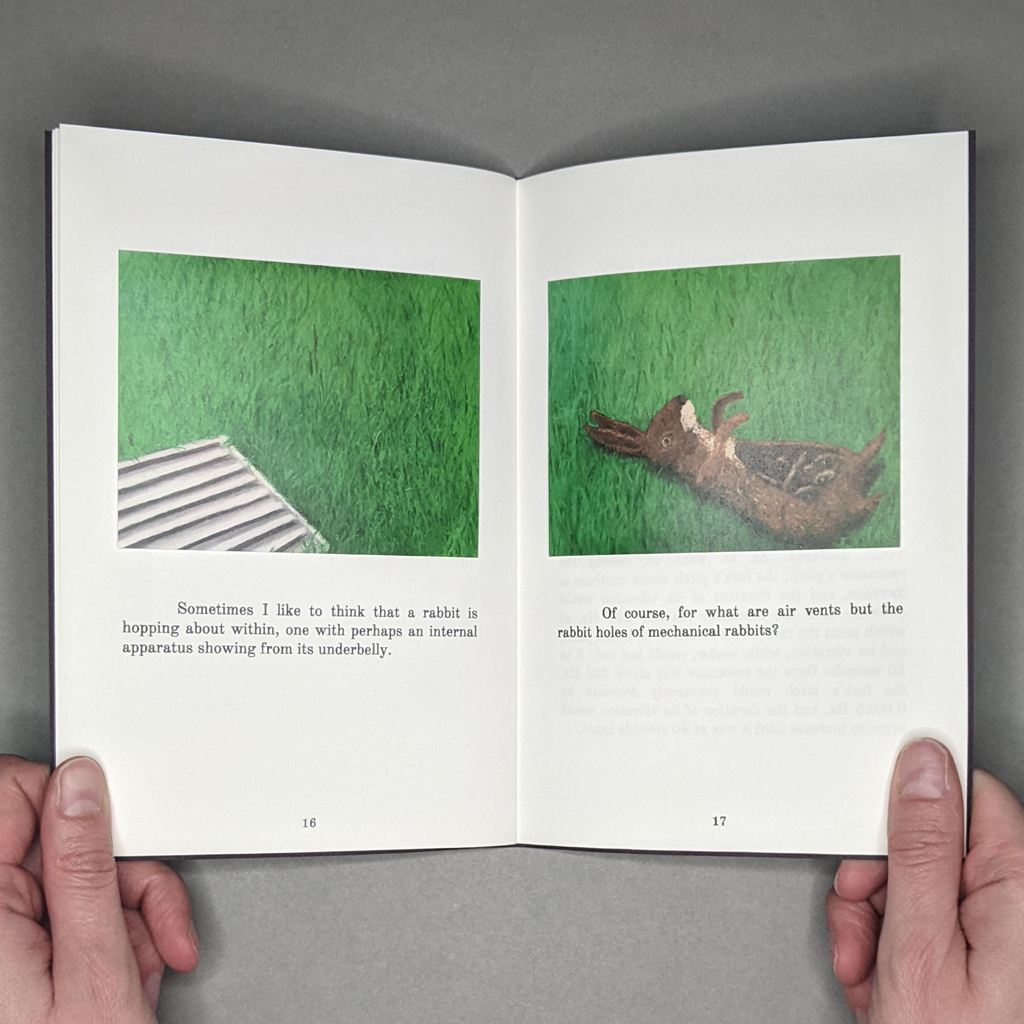

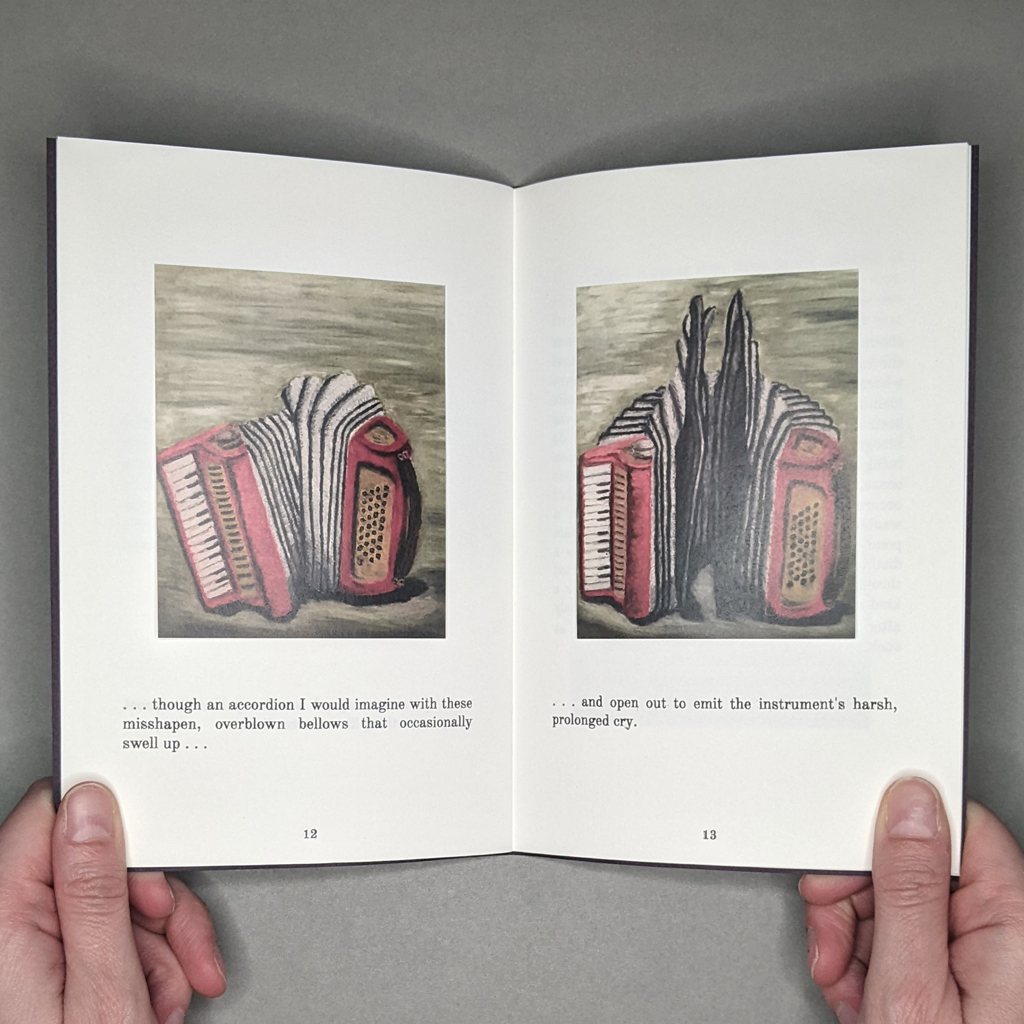

Finally, Majeski turns to an ekphrastic treatment of Oram’s music, leading to the sort of speculative interplay of image, object, and imagination that characterizes The Last State or the Penultimate. Over three pages, Majeski renders Oram’s percussive composition, In a Jazz Style, as a painted accordion that contorts and convulses, then lets out a “harsh, prolonged cry.” Now attuned to the music of everyday sounds (Oram samples dripping water, traffic noise, power tools, and the like), Majeski is free to interpret his own vernacular soundscape. He introduces a particular air vent near his home, whose grimy grating in the tipped-in photograph is at odds with his appeal to the reader to place their ear against the metal. To Majeski, the vent’s metallic pounding evokes a mechanical rabbit in the ductwork, all of which is duly illustrated on the following pages.

From the poetic attunement of the young music listener to the absurd image of a mechanical rabbit, the subject of Music of the Uncanny Soundscapes might be analogical thinking itself. Majeski’s abstract visualization of Oram’s composition Contrasts Essonic is a reminder that music is a metaphorical, not mimetic, art. Even the book’s seemingly literal illustrations reveal the limits of mimesis. Beneath a painting of an accordion, a line of text reads: “In many ways, I would say that it almost sounds something like an accordion….” Majeski’s qualifications — almost and something like — are moot, because even a perfectly accurate painting of an accordion tells nothing of its sound. The following page continues: “…though an accordion I would imagine with these misshapen, overblown bellows that occasionally swell up….” The painted accordion above this line is physically distorted, but the ambiguous word choice is telling — are the overblown bellows a part of the instrument, or are these sonic bellows swelling up, leading to the harsh cry on the following page? If music cannot represent like visual art, neither can visual art fully represent music. Sometimes hearing things and seeing things means imagining them.

In the postscript, Majeski returns to tuning forks, summarizing Oram’s discussion of nineteenth-century experiments by Rudolph Koenig. In these experiments, Koenig used a resonator to alter the pitch of a tuning fork. Subtly raising the pitch of the resonator (the receiver) caused the frequency of the fork (the transmitter) to decrease, and vice versa. The agency of objects is a major theme throughout Majeski’s series, and the notion of attunement rather than attention implies a reconfiguration of the sensing subject to accommodate the object. In fact, my review of Curious Details in Postcards questioned just how much agency the reader has in the face of a book’s careful manipulation of image, text, and sequence. Yet, Music of the Uncanny Soundscapes offers a rejoinder: the receiver also influences the transmitter.

Leave a comment