Shannon Davis

Controlled Burn

2022

4.5 × 2.75 × 1.5 in. enclosure

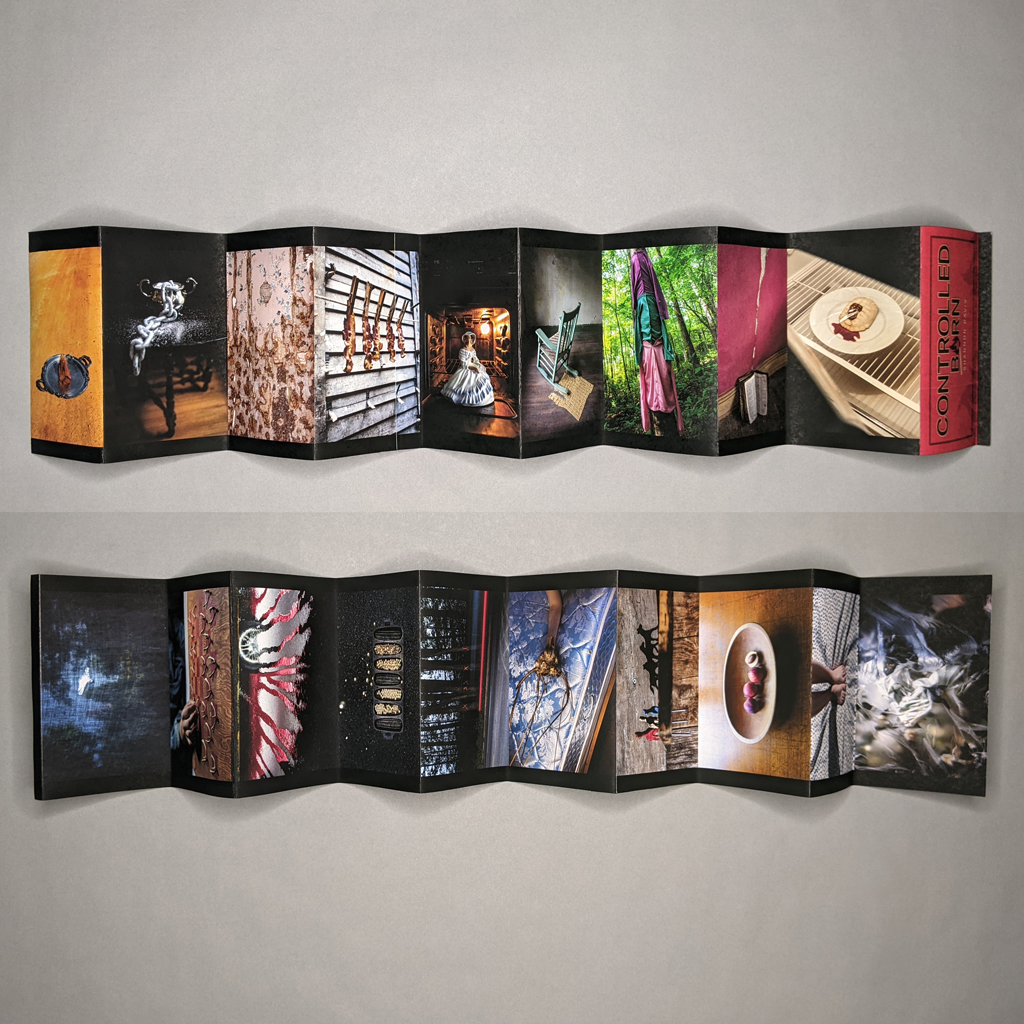

Accordion (4.5 × 25 in.) and 6-page drum-leaf pamphlet (4.5 × 2.5 in.)

Ink jet

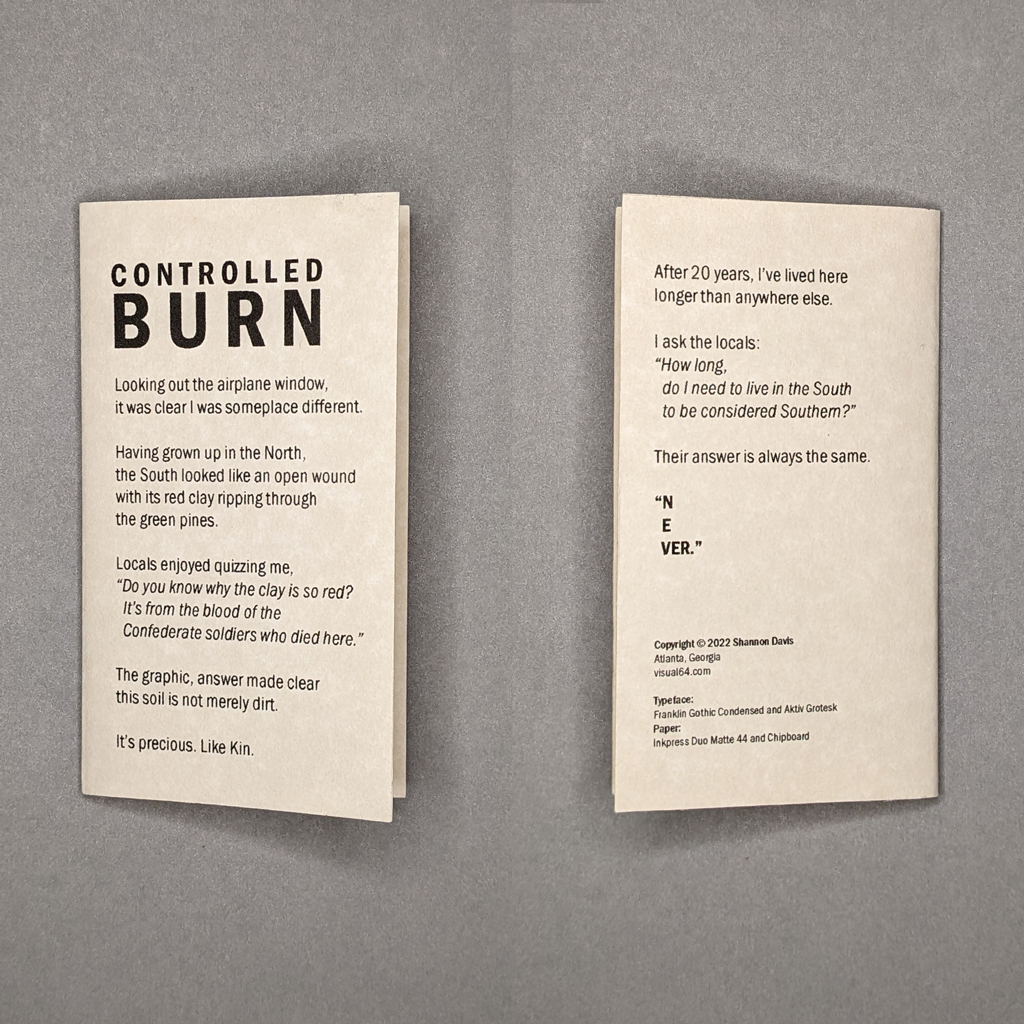

Controlled Burn is a photographic artists’ book drawn from a larger series of photographs. The two-sided, ink jet-printed accordion book is housed in a faux matchbox enclosure made of chipboard and wrapped with printed paper. The photographs, one per panel, are dark and saturated — visually but also figuratively. They are clearly staged and loaded with symbolism, even if the meaning isn’t immediately obvious. The accordion has no text, but Davis includes a small pamphlet with the book’s colophon and a poetic, first-person narrative text. In it, Davis reflects on the impossibility of a Northerner like herself fully assimilating into her chosen home in the US South. After twenty years in the South, but still not feeling at home — literally unheimlich — it is the uncanny that Davis explores in Controlled Burn.

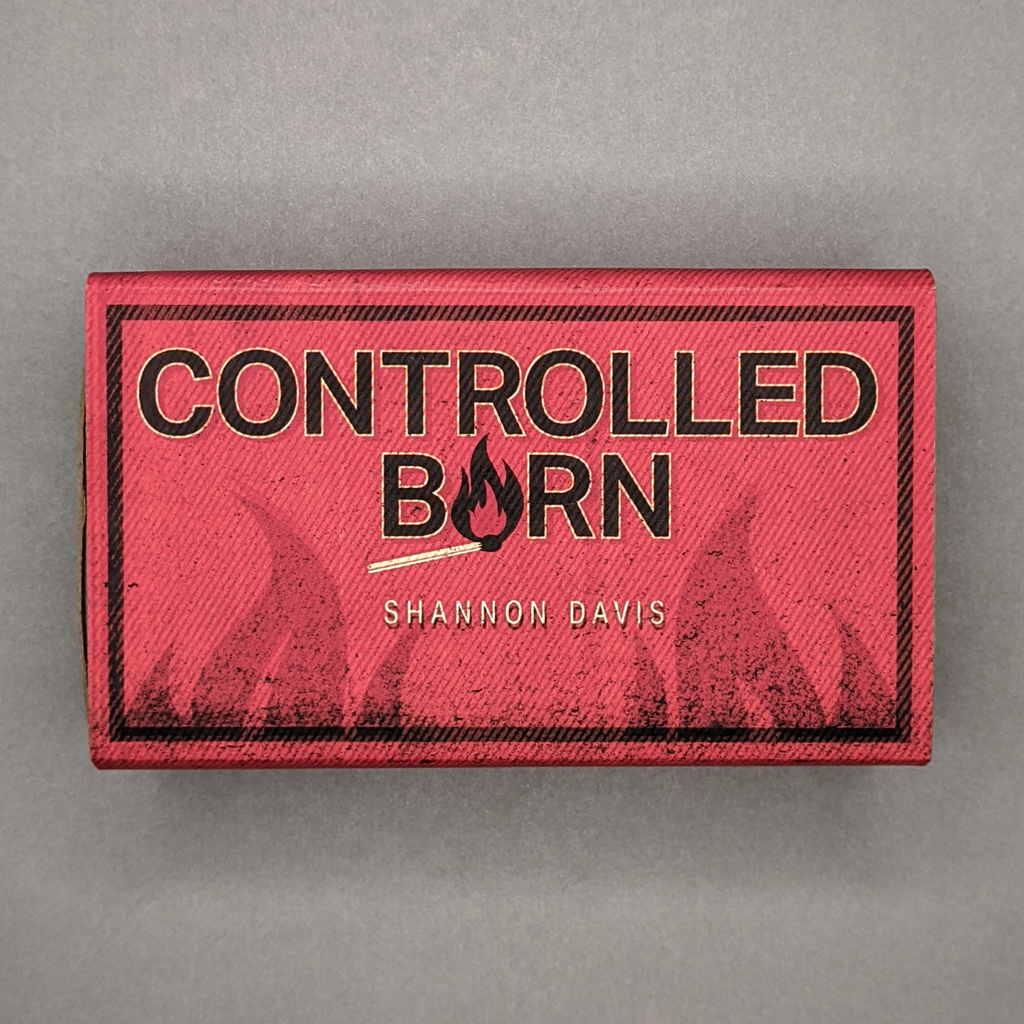

At first glance, the book’s enclosure passes as a matchbox. The hip, vintage-inspired design of the slipcase would make sense for a product that is all but obsolete, and Davis has gone as far as printing false striker strips on the front and back. The bottom tray of the box has an on-laid photograph of a pile of spent matches, with one in focus, as if the reader is holding the burnt matchstick before discarding it with the rest.

The front of the accordion repeats the enclosure’s cover images and includes a folded lip to facilitate easy extraction from the chipboard tray. Pulling on this lip, the reader reveals one horizontal image at a time, the accordion remains in the box until the final fold, thanks to its snug fit. On the reverse, the images are vertical. This simple change in orientation optimizes the reading experience, from the tentative, one-handed unboxing to the subsequent two-handed thumbing and stretching. Even fully extended, the book is easily held at a comfortable reading distance.

One consequence of this relatively small size (governed, it would seem, by the matchbox) is that the reader must look very closely at the images. Fortunately, the printing is high resolution. The colors are saturated, but the values are dark, and, in many images, a subtle vignetting pulls the eye toward the center. Their small size and shallow depth of field, combined with the black border running along the top and bottom margins, further gives the sense that the photographs are self-contained objects. The reader’s eye is drawn from one to the next not by visual movement or connection, but by compositional elements that echo one another. The book works through juxtaposition more than narrative continuity.

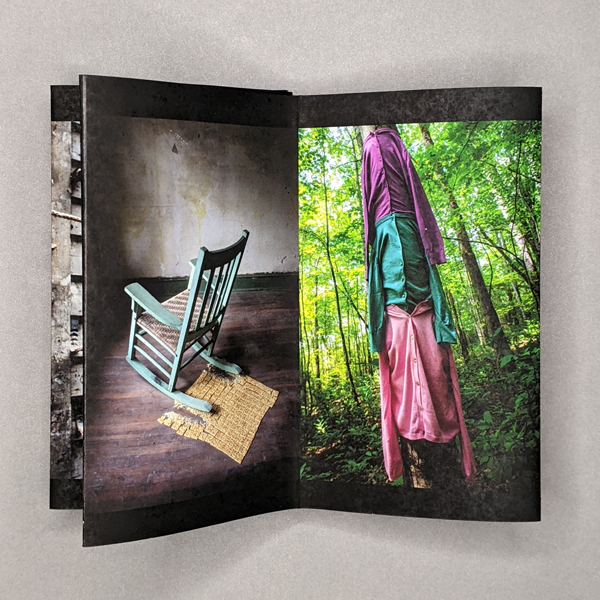

These echoes contribute to the sense of uncanny, the return of the repressed. The images themselves are highly constructed visual metaphors, Southern Gothic meets surrealism. Davis combines unexpected elements, often manmade and natural. A tree is dressed in a column of blouses, their empty sleeves hang eerily and rest on the shoulders of the blouse below. The spindly root ball of a plant seems to grow out of a human arm. Resting on an uncovered mattress, the assemblage looks more like a deer hunter’s taxidermy trophy. The images are almost uniformly unsettling, and their darker connotations creep into those that might otherwise seem neutral.

This overall mood is important, but the images also denote specific messages. If these are visual puns, one is reminded that jokes are the conscious expression of something suppressed. A toy football replaces the pit of a sliced peach (Davis lives in Georgia). An empty rocking chair crunches a carpet of crackers. A clod of earth is served on a silver platter in the middle of a red dirt road. Even as Davis reckons with her outsider status, the reader must rely on their own stereotypes of the US South to make meaning. However, the images are complex enough to remain open ended. And the abject constructions — crushed crackers on the floor or strips of bacon pinned to a clothesline — are at least as visceral as they are cerebral; the pun is rarely the punctum.

The fraught mood is both personal and political. Controlled burn is Davis biting her tongue to get along in the South, and it is also the racial tensions that still simmer just beneath the surface there. (Of course, racism is not uniquely Southern, and the stereotypes Davis plays with are one way that the rest of the country represses its own problematic histories.) Davis references both the personal and political in the pamphlet’s text, but she also notes that controlled burns are protective and restorative; they prevent uncontrolled fires and add nutrients to the soil. What then to make of the spent matches pictured in the book’s enclosure? Are we running out of controlled burns before a bigger fire erupts? Or could these matches catalyze a more fundamental change?

The duality of fire, both destructive and restorative, mirrors the narrator’s own ambivalence. She wants to be accepted by her community, but also wants to change it. Perhaps, then, it is this desire for acceptance that returns in Davis’s uncanny images as much as the repressed history of the South. A related duality plays out in the book, between content and structure. Each photograph forms a stable, coherent scene. Indeed, formal strategies like vignetting ensure that the images remain separate despite the accordion’s physical continuity. At the same time, the visual echoes among the photographs erode their integrity. What seemed wholly separate begin to feel like repeated flares from the same smoldering fire. Ultimately, Davis pitches the connectivity and circularity of the accordion against the autonomy of her carefully constructed photographs.

Controlled Burn is not just a collection of uncanny images. The book is a sophisticated exploration, a visual and material enactment, of a complex psychological experience. The reader is confronted, cerebrally and viscerally, with the desire to belong, the struggle to fit in, the telling of certain stories, and the repression of others.

Leave a comment